He would, wouldn’t he?

For two years in the early sixties Mandy Rice-Davies, the girl with the bit-part in the profumo affair, lived at 1 Bryanston Mews West in Marylebone not far from the Edgware Road. It was owned by the infamous slum landlord Peter Rachman and featured a two-way mirror and a tape-recorder under the bed.

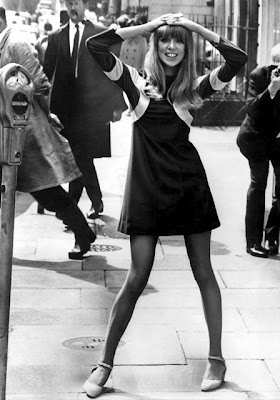

Rice-Davies initially came down to London from her family home in Sollihull in 1960. Although just sixteen she was Miss Austin for the launch of the new mini at the Earl’s Court Motor show. She was impressed with the glamourous receptions and parties that went with the week of modelling and soon decided to move to London permanently. She found herself a job as a showgirl at Murray’s Cabaret Club in Soho, an intimate club for 110 guests with deep-red carpets and gilt furniture. It was a place where topless showgirls mingled with gangsters, celebrities and royals – it was said that Princess Margaret was a member.

It was at Murray’s that that Mandy met Christine Keeler, one of the protagonists of the Profumo affair – ‘It was dislike at first sight,’ Rice-Davies recalled, and the feeling was mutual. However they both found themselves at the same parties and the two became close friends, working well together and seemingly complimenting each other – Rice-Davies was shrewd and had a head for money, Keeler did not and was generally disorganised. They also worked well in the bedroom, bringing them money for expensive clothes and lifestyles.

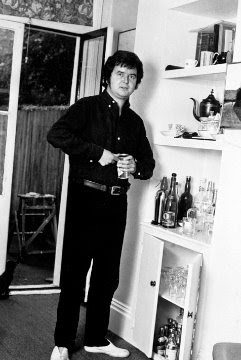

Stephen Ward 1963

Stephen Ward 1963It was Christine Keeler who introduced her to Stephen Ward, the well-connected osteopath and pimp and it was through him, and the orgiastic parties he organised, that she met many powerful politicians including Viscount Astor – a member of MacMillan’s Government in the early sixties. These characters became the major players in probably the greatest, well the most fun anyway, political scandal of the 20th century – the Profumo Affair.

John Profumo 1963

John Profumo 1963

Rice-Davies, ironically, never actually met John Profumo although she will always be connected to the scandal because of her brilliant, withering and pithy riposte to the prosecution council – “He would, wouldn’t he?” when told at Stephen Ward’s court case that Viscount Astor denied ever having slept with her or even having ever met her. This brazen riposte perfectly summed up the public’s perception that the Establishment was riddled with hidden scandal and hypocrisy. At the end of the trial Stephen Ward couldn’t prove that Mandy Rice-Davies and Christine Keeler’s rent hadn’t come from the proceedings of prostitution and he was was convicted on two counts. On bail, Ward killed himself on the last day of the trial before hearing the inevitable verdict.

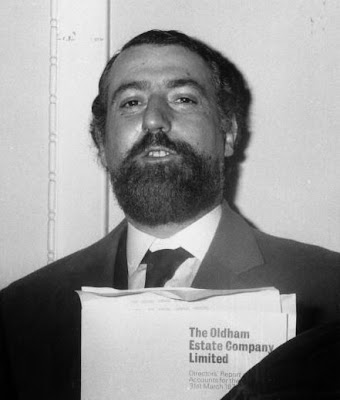

Mandy Rice-Davies had been the mistress of Peter Rachman a man now so infamous that his name is included in English dictionaries – ‘the exploitation and intimidation of tenants by unscrupulous landlords.’

Mandy was introduced to Rachman by Stephen Ward (they had been partners in a failed topless coffeebar venture) soon after she had arrived in London, and although their affair began on a professional basis it apparently turned into a pretty genuine relationship. Christine Keeler described them as “well matched, they had a material happiness together.”

Unlike his other girls the 17 year old Mandy accompanied him on visits to the theatre, opera and even Wimbledon and also hostessing his gambling sessions attended by aristocrats and gangsters. Rachman, by all accounts, was a pretty unpleasant man and looked, not unlike, an Ian Fleming villain. He was short and fat, with very tiny hands and feet, no neck and a head that looked like a football. He also had a fetish about hygiene insisting that all his silverware be sterilised and untouched by human hands.

Rachman became ill towards the end of 1962 and on November 29 died at Edgware General Hospital with his wife Audrey at his bedside after a second heart attack. It was assumed by everyone who knew him that he would be very rich, but after the creditors had picked the bones of his estate it was valued at a mere £8000. His property empire was just an elaborate juggling act and with his death the balls all came tumbling down. Even his Rolls Royce was on HP with instalments overdue.

Mandy Rice-Davies had just returned from Paris and although she had recently finished her affair with Rachman, immediately fainted when told of his death by Stephen Ward. When she came round the first thing she said was “Did he leave a will?”

Rachman’s infamy, it could be said, came by chance when his name was connected to the the Profumo Affair. He was already dead from the heart attack when the scandal had reached its peak and by the time he died Rachman had practically extricated himself from his slum empire. Even the rent tribunals with their horrific evidence had remained unreported in the press.

If he had chosen any other girl than Mandy Rice Davies as a mistress, subsequently letting her live in his Marylebone mews flat from where she and Christine often operated, the chances are his name today, other than mentions in obscure housing-law, would be completely unknown.

Unlike Christine Keeler, who never really recovered from the notoriety the Profumo Scandal accorded her, Rice-Davies revelled in the publicity, eventually marrying an Israeli businessman, Rafi Shauli. She went on to open a string of successful nightclubs in Tel Aviv called Mandy’s, Mandy’s Candies and Mandy’s Singing Bamboo. Rice-Davies also sang on a few unsuccessful pop singles for the Ember label in the mid-’60s.

With an obvious way for words, she once commented “My life has been one long descent into respectability.”

The music is from an album called

The Girls From Ember buy it

hereThis is my new guru: Magic Alex

The Apple Boutique at 94 Baker Street in Marylebone opened at 8.16pm, Monday 4 December 1967 (the exact time John Lennon, for some good reason or other, decided it should open). The Beatles had commissioned the Dutch design group The Fool to design the shop and one of the first things they did was to paint the outside of the building using a team of art students.

The Beatles asked a man called Alexis Mardis, known to their entourage as ‘Magic Alex’, to design the lighting for the shop, and one thing he promised was an artificial ‘sun’ using laser beams that would light up the sky during the boutique’s gala opening. Unfortunately, and to no surprise to a lot of people who weren’t taking the same amount of hallucinegic drugs the Beatles were, the artificial Sun did not materialise. It wasn’t, however, until about a year later that the Beatles realised that practically anything Magic Alex promised to invent or produce, failed to get passed the drawing board, or indeed even get on to a drawing board.

Throughout most of 1967 The Beatles as a group, and especially John, were heavily into psychedelic drugs, particularly LSD. In the early part of the year, John Lennon was at a party where he was given some LSD by Alexis Mardas. While Lennon was feeling the psychedelic effects, Alexis took the opportunity to describe to John his interest in electronics (in actuality his ‘expertise’ came only from being a former TV repairman), describing a variety of things such as car paint that would change colour at the flick of a switch, an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations that would shield the Beatles from the screams of their fans and electronic wallpaper that would make any room into a huge loudspeaker.

Throughout most of 1967 The Beatles as a group, and especially John, were heavily into psychedelic drugs, particularly LSD. In the early part of the year, John Lennon was at a party where he was given some LSD by Alexis Mardas. While Lennon was feeling the psychedelic effects, Alexis took the opportunity to describe to John his interest in electronics (in actuality his ‘expertise’ came only from being a former TV repairman), describing a variety of things such as car paint that would change colour at the flick of a switch, an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations that would shield the Beatles from the screams of their fans and electronic wallpaper that would make any room into a huge loudspeaker.

Mardas was patently charismatic, and given the inventions he described and John’s mental state, Lennon decided that he liked Magic Alex and befriended him. He soon introduced him to the rest of the Beatles: “This is my new guru: Magic Alex” he said. McCartney was surprised at this but later wrote “Because John had introduced him as a guru, there was perhaps a little pressure on him to behave as a guru”. Alex soon became a major player in The Beatles ever-growing entourage and was actually the person who told Cynthia Lennon that John would be divorcing her while trying to seduce her at the same time. He ended up sharing a flat with Jenny Boyd, George Harrison’s sister in law and an employee at the Apple Boutique.

The Beatles created a division of Apple called ‘Apple Electronics’ especially for Magic Alex. Money was poured into the company but most people, especially George Martin, realised that he had just rudimentary electronic skills – the Beatles however trusted him. Mardas was given the job of designing the Beatles’ new recording studio in the basement of Apple Headquarters in Savile Row partly because he had told them he was able to produce the World’s first 72-track tape machine (remember an 8-track recorder in those days state of the art).

During the year Mardas gave regular reports on how he was doing (and apparently spending ten million pounds in the process) but when they required the new studio in January 1969 to record what was to become known as Let It Be, The Beatles found a set of cramped rooms with no talkback, no soundproofing, and no wiring between the studio and the control room. There was one crude mixing console that Mardas had built but that had to be thrown away after just one session. The group were livid and embarassed and Alex was largely dismissed from their circle, disappearing relatively quickly into obscurity.

John’s letter inviting Magic Alex for dinner probably to explain ‘what the hell is going on?’

When asked to explain his involvement with The Beatles, Magic Alex said “Man is just a small glass, very, very clear, with many faces, like a diamond. You just have to find the way, the small door to each face.” I suppose if you’ve taken a shed-load of LSD that makes total and utter sense.

The Apple Boutique meanwhile closed for good at the end of July 1968. The local businesses had immediately complained about The Fool’s mural on the outside of the building and succeeded to get it removed by court order within a few months. On the inside, shoplifting had become rife – in the era of ‘love and peace man’ accusing anybody of stealing was incredibly difficult and rather uncool. In the end the shop was losing so much money it was agreed that it had to stop trading and the night before it did the Beatles and their closest associates came in and took what they wanted. The rest of the stock was given away the next day, it disappeared within hours as word got round and crowds enveloped the shop. The Apple Boutique was only open for nine months and it was around this time that The Beatles realised that not everything they touched necessarily turned to gold.

Roll up! Roll up! Everything’s free, man.

Mandy was introduced to Rachman by Stephen Ward (they had been partners in a failed topless coffeebar venture) soon after she had arrived in London, and although their affair began on a professional basis it apparently turned into a pretty genuine relationship. Christine Keeler described them as “well matched, they had a material happiness together.”

Mandy was introduced to Rachman by Stephen Ward (they had been partners in a failed topless coffeebar venture) soon after she had arrived in London, and although their affair began on a professional basis it apparently turned into a pretty genuine relationship. Christine Keeler described them as “well matched, they had a material happiness together.”

Throughout most of 1967 The Beatles as a group, and especially John, were heavily into psychedelic drugs, particularly LSD. In the early part of the year, John Lennon was at a party where he was given some LSD by Alexis Mardas. While Lennon was feeling the psychedelic effects, Alexis took the opportunity to describe to John his interest in electronics (in actuality his ‘expertise’ came only from being a former TV repairman), describing a variety of things such as car paint that would change colour at the flick of a switch, an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations that would shield the Beatles from the screams of their fans and electronic wallpaper that would make any room into a huge loudspeaker.

Throughout most of 1967 The Beatles as a group, and especially John, were heavily into psychedelic drugs, particularly LSD. In the early part of the year, John Lennon was at a party where he was given some LSD by Alexis Mardas. While Lennon was feeling the psychedelic effects, Alexis took the opportunity to describe to John his interest in electronics (in actuality his ‘expertise’ came only from being a former TV repairman), describing a variety of things such as car paint that would change colour at the flick of a switch, an invisible curtain of ultrasonic vibrations that would shield the Beatles from the screams of their fans and electronic wallpaper that would make any room into a huge loudspeaker.