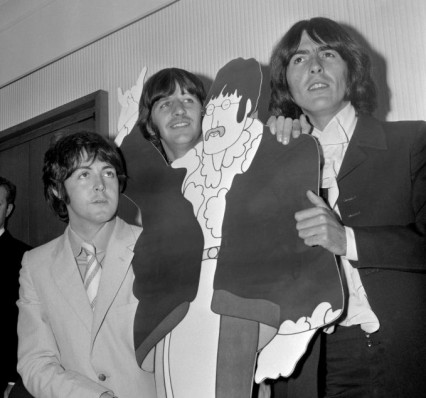

When the last chord of ‘Twist and Shout’ came to an end, the Beatles grouped together at the front of the Prince of Wales Theatre stage. The blue curtain swished closed behind them and, from the waist and in unison, they bowed first to the ‘cheap seats’, then turned and bowed again to the ‘jewellery wearers’ in the Royal Box. With the orchestra playing and the audience still applauding they skipped and ran off the stage with boyish energy.

It was the comedian Dickie Henderson, unenviably, who was next to perform, and after the applause had died down he said: ‘The Beatles … young … talented … frightening!’ The audience laughed, but it had been said with feeling. He, like most of the other acts on the bill of the Royal Variety Performance in November 1963, including Marlene Dietrich, who couldn’t understand why all the camera lenses had been pointing at the four young men from Liverpool, suddenly felt very old-fashioned.

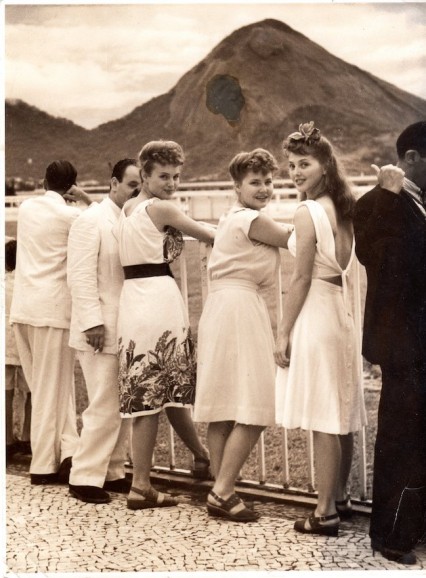

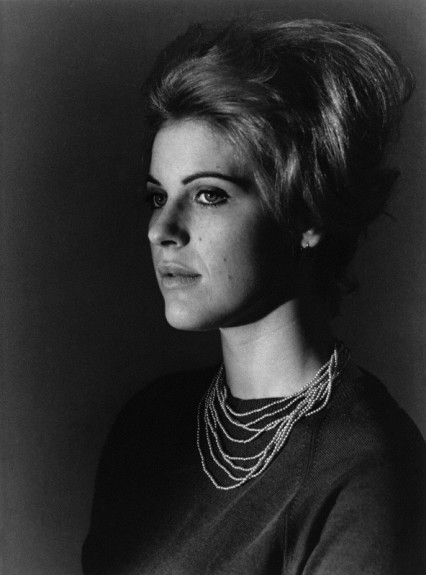

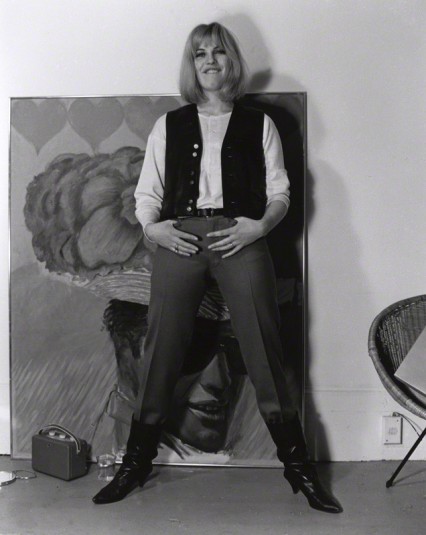

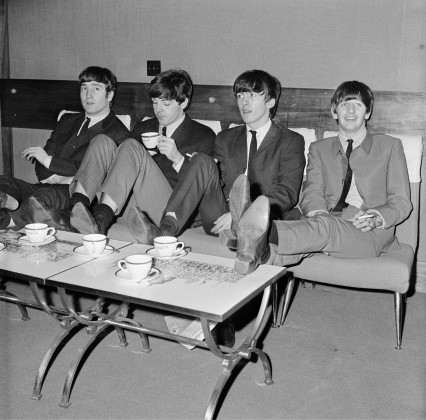

The Beatles relax backstage at London’s Prince of Wales Theatre, before the Royal Variety Performance, 4th November 1963. They are supporting Marlene Dietrich in the show. (Photo by Mark and Colleen Hayward)

Henderson’s fame was at its peak that November, and it was on purpose and as a reassuringly safe pair of hands that Bernard Delfont had asked him to follow the Beatles that night. The theatre impresario had had too many bad experiences with pop groups dying in front of indifferent mink-wearing Royal Variety audiences,and when he had booked the Beatles earlier that year, on the advice of his daughter Susan, he had never heard of them. The primetime Dickie Henderson Show had recently finished on ITV (it was a staple on the channel between 1960 and 1968) and that summer Henderson had been top of the bill of a popular show called Light Up the Town at the Brighton Hippodrome.

Today you would almost have to be a pensioner to remember Henderson in his prime, but he was once described by Roy Hudd as ‘perhaps the most versatile and certainly the smoothest, most laid-back comedian it had been my pleasure to see’, adding that ‘he danced, sang and delivered one-liners wonderfully, and even his prat-falls were, somehow, classy … He was, without doubt, the best I ever saw.’

Dickie had come from a ‘showbiz’ family. Before the First World War his sisters, Triss and Winnie, were a pair of popular dancers and singers called the Henderson Twins, while his father, Dick Henderson, was a rotund, bowler-hatted comedian and singer known in the music halls, where he had made his name, as ‘The Yorkshire Nightingale’. His trademark was his breakneck banter, salty and censorious, and delivered in a strong Hull accent. Part of his act was to tell the audience that he didn’t want any applause because he was there ‘strictly for the money’. He is perhaps most famous for the first British recording of ‘Tiptoe Through the Tulips’, with which, accompanying himself on the ukulele, he usually entered and exited the stage.

Dick Senior, like his son, also performed at Royal Variety shows, the first of which was in 1926 when King George V laughed at: ‘I went to get married and asked the vicar how much it was. He said, “What do you think it’s worth?” I gave him a shilling. He took one look at the bride and gave me twopence back!’

Henderson was a fat man and he usually started his performance by standing sideways, showing o his large belly, saying: ‘I was standing outside a maternity hospital, minding my own business … ’ He died in 1958, just a few days before what would have been his third Royal Variety show. Dickie Henderson’s first job in show business was, as a ten-year-old, playing Master Marriott in the 1933 film of Noël Coward’s play Cavalcade, a movie made while his father was in California performing in vaudeville.

Henderson Senior, despite losing most of his life savings in the Wall Street Crash, was earning reasonably good money in the States where he was commanding top billing in the smaller houses, and was a much appreciated feature act in the bigger circuit halls. Even though the popularity of vaudeville was on the wane, Henderson Senior often earned an impressive $1,000 per week. Dickie tells a story in his half-finished autobiography that Hal Roach had once offered his father, a stout gentleman who never performed without his bowler hat, to ‘test’ with Stan Laurel, another Englishman from the north of England. His father turned him down, however, as the money was only half of what he was earning on stage. Henderson Senior always regretted this decision but later admitted that, compared with Oliver Hardy, ‘I would never have been as good.’

Henderson Senior did make a few films, however, including The Man from Blankley’s in 1930, which starred Loretta Young and John Barrymore, now unfortunately lost. It wasn’t necessarily an easy life in Hollywood at that time, despite the warm Californian sunshine. Noël Coward, unhappy that everyone seemed to ‘work too deuced hard’, once described a typical day while working on Cavalcade: ‘They get up at 6.30 … stand around all day under the red-hot lights … eat hurriedly at mid-day, and because they are too tired to sit up, late at night have their supper served on trays. That’s no way to live, and certainly no way to work.’

After the young Dickie had completed his part on Cavalcade, for which he earned $400 for the month’s work, the whole family returned to England on the liner RMS Lancastria. Ten years later, on 17 June 1940, the Lancastria, sank in twenty minutes after it was bombed by the Luftwaffe near the French port of Saint-Nazaire. The sinking of the Lancastria has almost been forgotten but it was the largest loss of life from a single engagement for British forces in the Second World War – about 4,000 men, women and children died. It was also the largest loss of life in British maritime history – greater than the Titanic and Lusitania combined.4 Dickie left school at fifteen, and became ‘prop boy’ with Jack Hylton’s Band, with whom his twin sisters, two years his senior, were singing.

Two years later, the twins had become ‘headliners’ throughout the country and Henderson was learning everything about stagecraft, which he would put to good use for the rest of the career. Looking back at this time he once wrote:

The time on the road, when not performing, we spent learning. Every morning jugglers, acrobats, dog acts and dancers rehearsed. Always rehearsing. In exchange for dance steps from dancers, the jugglers taught dancers how to twirl a cane. Acrobats put you in a harness and taught you back-somersaults. That is why performers, then, could do a bit of everything. I was fortunate to have been part of it, before ‘that school closed’, to quote the great Jacques Tati.

In September 1939, at the start of the Second World War, all the theatres were instructed to close. Dickie became a messenger boy with Air Raid Precautions (ARP), given a bicycle and told to await instructions. There never were any instructions, and when the theatres reopened, after just two weeks, he was back to his pre-war life and travelling around the country as a junior touring performer.

Just as he was about to appear, along with Naunton Wayne and the Hermiones Gingold and Baddeley, in A La Carte, his first West End show, Henderson was called up. It was 1942 and he was nineteen. In the next three years he had, in his own words, ‘an extremely cushy war’. He didn’t have to leave Britain and he saw no action.

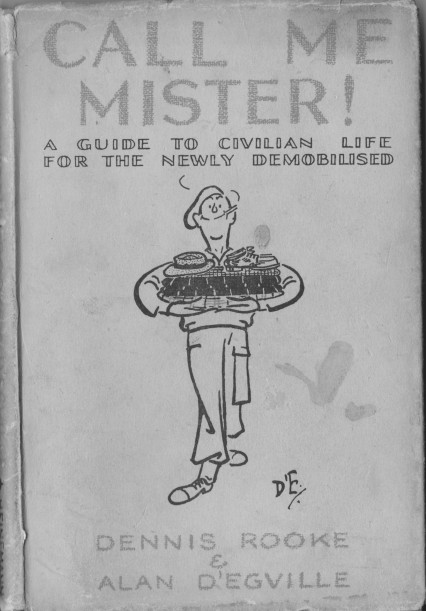

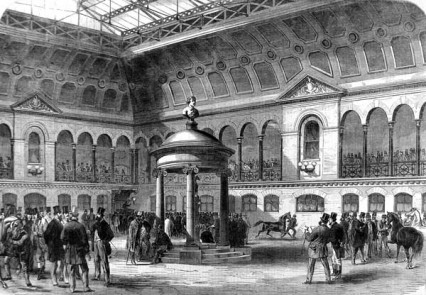

Second Lieutenant Dickie Henderson wasn’t able to re-join civilian life until 1946. He was just one of over 4 million servicemen who were demobilised between June 1945 and January 1947. Like thousands and thousands of others, he made his way to Olympia to swap his service uniform for the ubiquitous ‘demob’ outfit. Most of the servicemen in the queues were grumbling about the length of time it had taken for them to get there. The first illustration in the book Call Me Mister! – A Guide to Civilian Life for the Newly Demobilised was a cartoon of an old and decrepit man holding his release book and saying, ‘To think I should really live to see myself demobbed.’

By the end of 1945, 75,000 de-mob suits were being made every week and supplied by tailors such as Burtons, a company founded by Montague Burton and where, perhaps, the phrase the ‘full Monty’ came from – meaning the full set of demob clothes supplied by the firm. Anthony Powell, who served in the Welch Regiment and later the Intelligence Corps during the war, used a scene set in the demob centre at Olympia in the closing passages of his 1968 novel The Military Philosophers: ‘Rank on rank, as far as the eye could scan, hung flannel trousers and tweed coats, drab mackintoshes and grey suits with a white line running through the material’. He pondered whether the massed ranks of empty coats on their hangers somehow symbolised the dead.

The ‘full monty’, as it were, included socks, a shirt, a tie, a hat, cu links and collar studs and came in a ‘handsome box bound with green string’. The accompanying label featured the magic word – to men who had been in the services for six or more years anyway – ‘Mr’, followed by their name. The de-mob suit, often ill-fitting due to the lack of the right sizes available, was a subject to which literally millions of people could relate and became an important ingredient of much post-war comedy. The comedian Norman Wisdom, whose suits were always far too tight with ‘half-mast’ trousers, had been demobilised in 1946 and was once described by John Hall in the Guardian as ‘Pagliacci in a demob suit’.10 Frankie Howerd, yet another of the generation of British comedians who came to prominence in the years after demobilisation, performed in a badly fitting demob suit, probably because, like countless others, he had nothing else to wear.

Dickie himself described his new demob clothes as a ‘grey double- breasted three-piece pinstripe suit, snap trilby hat and a flannelette shirt a air, rather like pyjamas’. He also mentioned his ‘cumbersome shoes’, and it was often joked by the new civilians that the footwear provided by the government needed to be particularly stout and rugged to stand up to the constant wear and tear as they tramped around endless pavements in search of suitable employment.

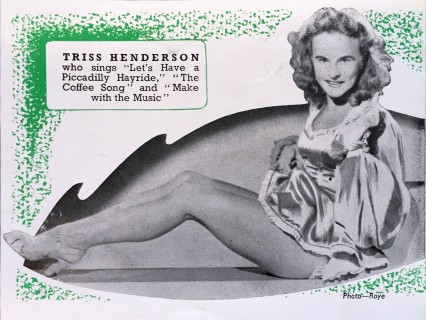

After his visit to the Olympia De-Mob Centre, Dickie later wrote about how embarrassed he was of his new civilian clothes when, walking down Piccadilly on his way to see his sister Triss, he bumped into a snappily dressed Jack Hylton, who was wearing a suit from Hawes and Curtis in Jermyn Street, a Sulka shirt from the shop on Old Bond Street, and shoes by Walkers of Albermarle Street. Triss Henderson, who had sung with Hylton but was now dancing solo after her sister had met and married a GI during the war, was appearing in a revue called Piccadilly Hayride at the Prince of Wales Theatre. The same theatre, located on Coventry Street between Piccadilly Circus and Leicester Square, where Dickie would be compering the 1963 Royal Variety show seventeen years later.

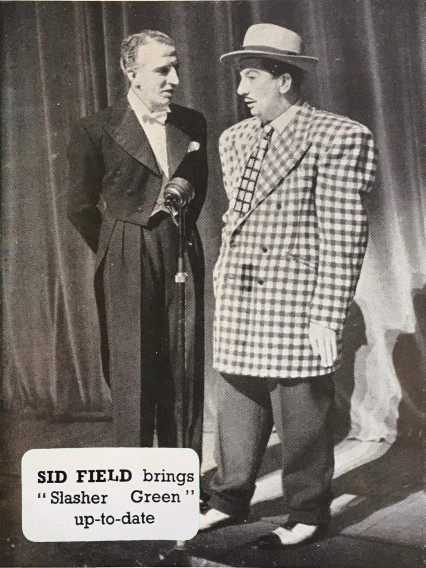

The Piccadilly Hayride revue at the Prince of Wales Theatre, where Dickie’s sister Triss Henderson was performing, was actually the comedian Sid Field’s triumphant return to the stage after the disappointment of the expensive technicolour film London Town released the previous year. Much to Field’s relief, the disastrous reception of the movie didn’t at all damage the mutual love affair he now had with the West End audiences and theatre critics and it cemented his reputation as perhaps one of the greatest comedians ever to appear on the West End stage.

Preceding Field’s first sketch of the show, entitled The Return of Slasher Green, Triss Henderson performed the opening song called ‘Let’s Have a Piccadilly Hayride’ with fellow performer Pauline Black, the daughter of the theatrical producer, George Black. At Al Burnett’s nightclub The Stork, just off Regent Street, Pauline introduced Dickie to a young woman called Dixie Ross, part of an extraordinary American singing, dancing and contortionist act called the Ross Sisters (‘Pretzels with Skin’ said some of their posters).

Dixie Jewell Ross was just sixteen and along with her two elder sisters, Veda Victoria Ross and Betsy Ann Ross, eighteen and twenty years old respectively, had travelled to Britain on the RMS Queen Mary, docking at Southampton on the 10 September 1946. Each sister, presumably so they could perform ‘legally’ in clubs in the US and subsequently the UK, had assumed the identity and birthday of the next older sister, and carried passports to this effect. The eldest of the trio, Eva, managed this by taking the name and birth date of Dorothy Jean Ross, the first-born sibling, who had died just a few months old of whooping cough in 1925. Informally the sisters continued to use their original given names, but formally their ‘legal’ names became Dorothy Jean, Eva V and Veda V. Confused? You will be, because the Ross Sisters often used the stage names of Aggie, Maggie and Elmira.

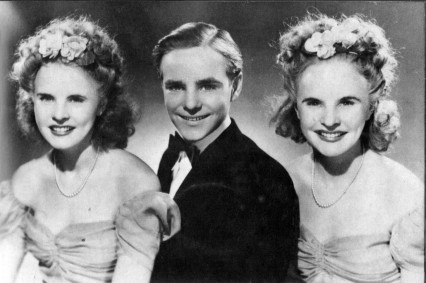

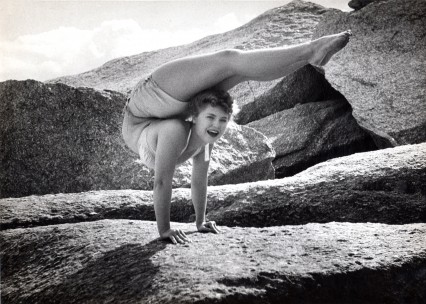

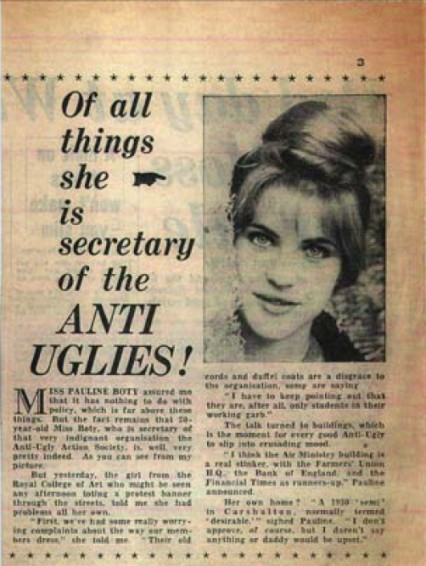

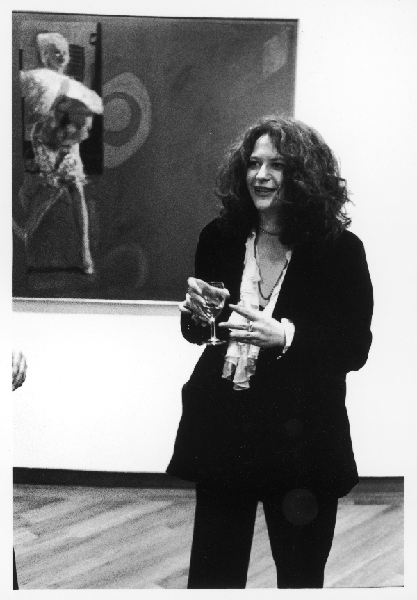

1th September 1946: Actress sisters Betsy, Vicky and Dixie Ross at Waterloo Station, on arrival in London on the Queen Mary boat train. They are to appear in the new Sid Field show ‘Piccadilly Hayride’.

Whatever they were called, just four years previously the girls and their parents were all living in a trailer near New York. The Ross Sisters’ parents were originally very poor dirt farmers from west Texas. When the dust storms drove them off the land,Mr Ross started working on the Texan and Mexican oil fields, while the girls’ amateur acrobatics were good enough to perform at county fairs and such like. Eventually they were good enough to appear in theatres around the country, and they pooled their money and bought a trailer.

In 1942 they got their big break, being asked to join the cast of Count Me In, a musical starring Charles Butterworth at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on Broadway. In the evenings the girls were appearing in a Broadway show while living in a trailer parked at Ray Guy’s Trailer Park, Bergen Boulevard, which is about a mile across the George Washington Bridge in New Jersey. American syndicated newspapers reported that they were ‘thrilled about their first trip to New York. “But,” says Betsy, who is twenty and the eldest, “we certainly aren’t going to give up our trailer until we are sure of the future.”’

The Texan-born sisters had been invited to the West End by Val Parnell, the managing director of the Moss Empire theatres network, who thought they’d work really well in Piccadilly Hayride. Parnell had seen the Ross Sisters’ performance in a film called Broadway Rhythm, an MGM hodgepodge of a musical released in 1944. It starred Ginny Simms and George Murphy, who played a Broadway producer looking for big-name stars, while ignoring the talent around him from his family and friends. The film was essentially a pageant of various MGM speciality acts, including impressionists, nightclub singers and tap dancers.

The short New York Times review of the film included the line: ‘Three little girls, the Ross Sisters, do a grand acrobatic dance.’ The ‘grand acrobatic dance’ is pretty well all that’s remembered of the lm these days, and seventy years or so after the lm was released, their remarkable performance has been seen by millions on Youtube and certainly by many more people than on its original cinema release in 1944.

The extraordinary performance by the Ross Sisters in Broadway Rhythm

If Broadway Rhythm wasn’t particularly successful, Piccadilly Hayride, riding on Sid Field’s incredible popularity, certainly was, and it ran for an incredible 778 performances and took over £350,000 at the box office. The original songs for the revue were written by Sammy Cahn and Jule Styne, one of which, ‘Five Minutes More’, was sung by the Ross Sisters, and a version by Frank Sinatra became one of the most popular songs of the year.

Dickie fell in love with young Dixie, and although he was performing in a touring revue entitled Something to Shout About (a title it didn’t live up to, according to Dickie) when he was in London he took her to nightspots such as the Coconut Grove at 177 Regent Street – a club where the Latin American bandleader Edmundo Ros had performed during the war. Dickie would later appear in cabaret there, and describes it in his autobiography: ‘It was like all night-clubs at the time: a cellar where one could drink scotch or brandy after hours out of a cracked co ee cup in case of a police raid. It was never raided during the three months that I was there, and with Savile Row police station only one hundred yards away, I drew my own conclusions regarding the dogged efficiency of the police surveillance.’

When Piccadilly Hayride closed, Dixie and her sisters went to France to perform at the glamorous Bar Tabarin on rue Victor Massé with the likes of Edith Piaf and Maurice Chevalier. Meanwhile, Dickie went into pantomime in Brighton with the double-act Jewel and Warriss. After the six-week run, a broke Dickie used up his last £10 for a flight to Paris and immediately proposed to Dixie. He assumed that, if she accepted, he had time to save some money as she and her sisters had planned to tour Australia for six months.

The next morning they strolled down the Champs-Elysées and Dixie turned to Dickie and said, ‘Darling, I have some wonderful news… ’ The middle sister, Vicki, had fallen in love with the French ventriloquist Robert Lamouret (who performed with a Donald Duck-a-Like called Dudulle and was also part of Piccadilly Hayride). He had proposed to her but she didn’t want to break up the act. ‘But she can now, as we are getting married too!’ said Dixie. Henderson and Dixie Jewell Ross married in the summer of 1948 at Westminster Cathedral, with the comedian Jimmy Jewel as the best man.

Exactly fifteen years later, on 10 July 1963, a few weeks before he followed the ‘frightening’ Beatles on to the Royal Variety stage at the Prince of Wales Theatre, Dickie Henderson arrived at his home in Kensington, only to be told his wife had died on the way to hospital. Dixie Henderson, at the age of thirty-three, and according to the coroner, had taken fifteen or sixteen barbiturate sleeping pills. She had left a note for the ‘daily’ saying that she wasn’t to be disturbed. Whether it was suicide or a tragic cry for help, the coroner gave an open verdict and it was noted that it had been Dickie and Dixie’s fifteenth wedding anniversary.

In fact Dickie hadn’t seen his wife for two weeks, and would write in his unfinished autobiography that they were on a trial separation at the time, and that he was actually returning home to discuss a reconciliation. Dixie was buried in Gunnersbury Cemetery in Acton. On the gravestone it says ‘Dixie’, but the marriage and death certifcate both have her name as Veda Victoria – the name she borrowed from her older sister twenty years before and never officially relinquished.

Invariably a safe pair of hands, the ‘classy’ Dickie Henderson went on to perform in eight Royal Variety shows. After making his television debut on Arthur Askey’s Before Your Very Eyes in 1953, he became a much-loved national star during the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s. Some forty-seven years after making his inauspicious stage debut as an ‘eccentric dancer’, the always neat and dapper Dickie succumbed to pancreatic cancer in 1985.

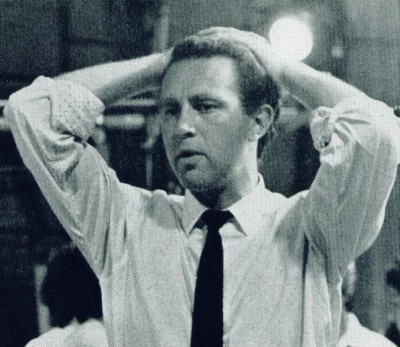

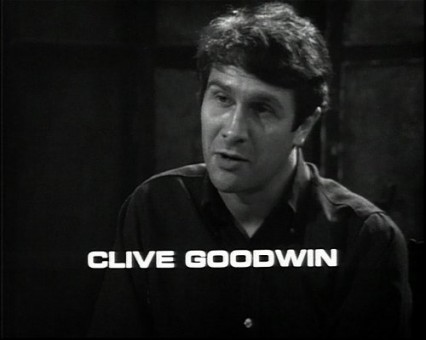

Dickie Henderson on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1959

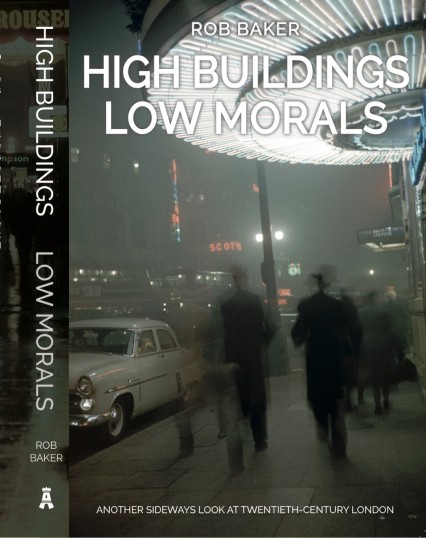

This is an excerpt from my new book called High Buildings, Low Morals and due to be published on 15 October 2017. Contact me by email or twitter if you’d like a signed copy. More stuff from me, occasionally about London, can be found at flashbak.com.