STOCKWELL ROAD isn’t the most exciting and handsome of roads. It may have been once, but the Luftwaffe and the subsequent, typical unimaginative post-war redevelopment put paid to that. It’s got a skateboard park, if that’s your thing, and David Bowie was born in a road just off it, but even he moved to Bromley when he was six. And that’s about it, to most people, even if they live there, it’s just a road that joins up Stockwell and Brixton.

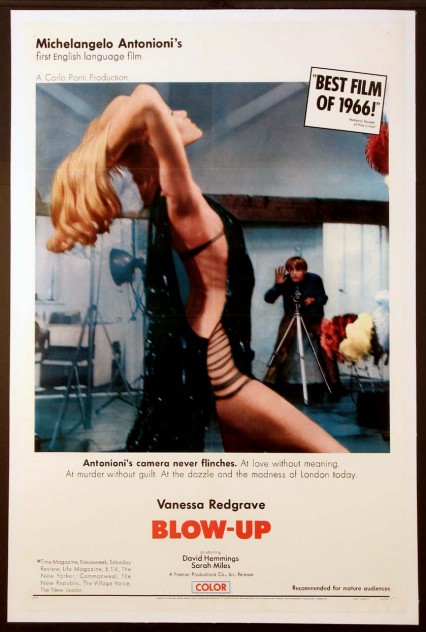

If you walk towards the Brixton end, however, and you stop and look carefully at the end of a terrace, you can see a tiny bit of maroon-ish red paint showing through some peeling cream emulsion. It’s the remnants of a lot of red paint and a clue that in the winter of 1966 this road made a glamorous appearance, alongside David Hemmings, the model Veruschka, and Vanessa Redgrave, in THE swinging Sixties film – Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up. It was the Italian director’s first film in English (he had just signed a lucrative deal to make three English-language pictures for Italian producer Carlo Ponti), and it was David Hemmings’ first major film role.

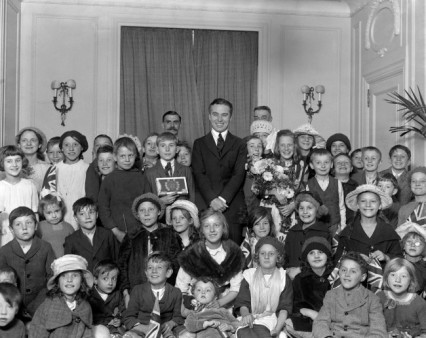

On stage, however, Hemmings had already been a star, of sorts. In 1954, thirteen years before Blow-Up was released, a twelve-year-old Hemmings had appeared, as a boy soprano, in Benjamin Britten’s opera The Turn of the Screw. To prepare for the role of Miles, in the as yet uncompleted opera, Hemmings had left school and his home in Tolworth, a southwest suburb of London, and had gone to live with Benjamin Britten at Crag House in Aldeburgh in Suffolk. ‘It was one of the most wonderful times of my entire life’ Hemmings once remembered: ‘we all gathered round the piano – Peter Pears, Jennifer Vyvyan, Joan Cross, Arda Mandikian, Olive Dyer and me … He really constructed the opera round our voices.’ Hemmings throughout his life never wavered from saying that Britten’s conduct with him was beyond reproach, at all times. In John Bridcut’s Britten’s Children Hemmings says:

He was not only a father to me, but a friend – and you couldn’t have had a better father, or a better friend. He was generous and kind, and I was very lucky. I loved him dearly, I really did – I absolutely adored him. I didn’t fancy him, I did go to bed with him, but I didn’t go to bed with him in that way.

Tenor Peter Pearsas Quint and child soprano David Hemmings (1941 – 2003) as Miles in the English Opera Group’s production of Benjamin Britten’s ‘The Turn Of The Screw’, 13th October 1954. (Photo by Denis De Marney

David Hemmings, aged 12 enjoying Venice (drinking water from a fountain) between rehearsals of Benjamin Britten’s new opera ‘Turn of the Screw”.

Just five weeks after Britten had completed the opera the British premiere took place on 6 October 1954 with the Sadler’s Wells Opera. It took place against a backdrop of increasing police antipathy to homosexuality. A situation not helped by the fervently anti-homosexual and moralistic Home Secretary Sir David Maxwell Fyfe. Three years previously, in 1951, the defection to the Soviet Union of Guy Burgess, who was as close to openly gay as you could be in those days, and the (almost certainly) bisexual Donald Maclean had also stoked up public hostility.

Prosecutions for ‘gross indecency’ were increasing and there had been several highly publicised arrests, such as Lord Montagu and John Gielgud. Britten was also interviewed by police officers in 1953 – he had been at school with Maclean and one of Guy Burgess’s boyfriends had lived at Britten’s Hallam Street flat in the 1940s – but nothing came of it. At one point, however, Britten discussed the possibility that his partner Peter Pears might have to enter into a sham marriage.

The end of Hemmings’ opera career with Britten came to a particularly abrupt end. The English Opera Group had taken The Turn of the Screw to the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris. It was 1956 and Hemmings was now fifteen. In the middle of Miles’ main aria, ‘Malo’, Hemming’s voice suddenly broke. Britten was utterly horrified and stopped the orchestra immediately. He waved his baton in anger at the now ex-soprano, and the curtain slowly lowered. Britten did not speak to, or even acknowledge Hemmings ever again.

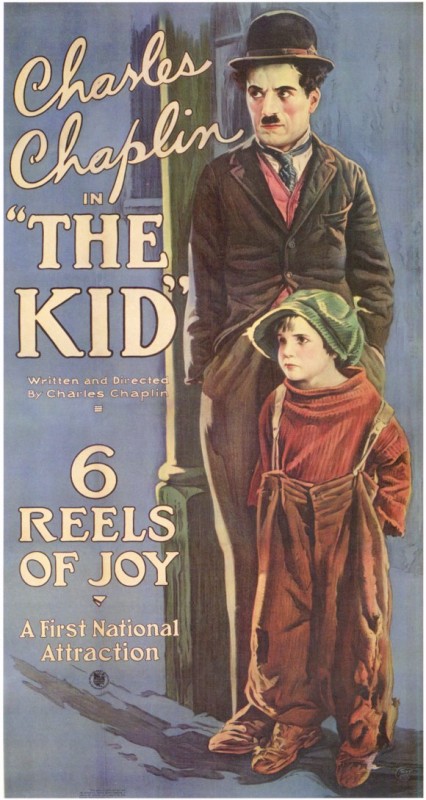

Ten years later Antonioni chose Hemmings for the role in Blow-Up because he wanted a fresh young actor who had no self-conscious acting style. The Italian director detested ‘Method’ acting, and in The Passenger, filmed in London in 1974 and the third of Ponti’s English language films, Antonioni kept on saying to Nicholson, ‘Jack, less twitching’. Antonioni once said: ‘Actors feel somewhat uncomfortable with me. They have the feeling that they’ve been excluded from my work. And, as a matter of fact, they have been.’ He first saw Hemmings act in an adaptation of Dylan Thomas’s Adventures in the Skin Trade, at a small theatre in Hampstead. A few days later, at the first audition for Blow-Up held at the Savoy hotel, and before the young actor had said a word, Antonioni told Hemmings, ‘you look wrong. You’re too young.’ Hemmings replied ‘Oh no. I can look older. I’ve done it before. You can trust me on this. I am an actor.’

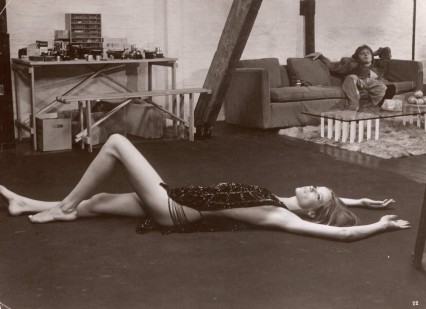

After one more audition, Antonioni did trust him, and Hemmings went on to play his most famous role – the ‘swinging’, hip fashion photographer, who discovers by accident that some photos he took seem to reveal a murder. The character was purposely based on David Bailey who in the mid-sixties was at the height of his fame. Even a scene where Hemmings buys a large old propellor in a junk shop was based on Bailey doing exactly that. At eight quid they even got the price right, much to Bailey’s shock when he was watching the film in New York with his new wife, Catherine Deneuve. Bailey was once asked whether his photo sessions ever got as sexy as the one between Hemmings and Veruschka. ‘When I was lucky,’ he replied.

The shoot for the film began in April 1966 and wherever the filmmakers went they left their mark on London. Antonioni thought the roads were a bit grey in Woolwich and had them painted black, and it was said that even pigeons were dyed so they were just the right sort of pigeons. The Rolls-Royce, once owned by Jimmy Savile, was originally white and the director had that re-sprayed to black. Antonioni once talked of his fastidious attention to detail: ‘When I was making Blow-Up there was a lot of discussion about the fact that I had a road and a building painted. Antonioni paints the grass, people said. To some degree, all directors paint and arrange or change things on a location, and it amused me that so much was made of it in my case.’

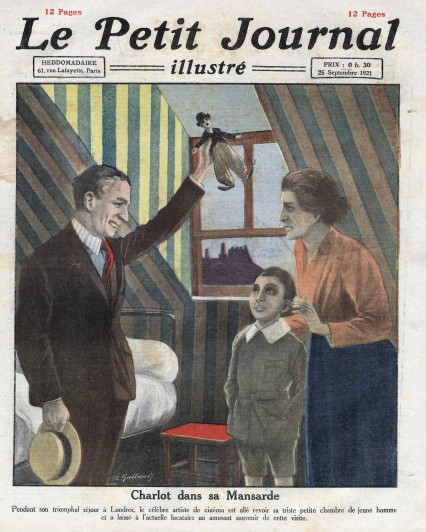

Most people thought that Antonioni was only up to his old particular ways when they watched Hemmings drive his Rolls Royce down a long terrace of Victorian and Edwardian buildings, all painted entirely red. The buildings, however, really were that colour and were made up of dozens of properties all owned by the motorcycle spares company, Pride and Clarke, and every one painted red.

The company was founded in 1920 by John Pride and Alfred Clarke and was based on the Stockwell Road for over sixty years. In its heyday the showrooms of ‘Snide and Shark’, as they were occasionally called, took up a huge stretch of the road and if the Guinness Book of records had ever been interested in motorbike spares’ counters, they would have featured Pride and Clarke’s because it was the longest in the world. With about 2000 new motorbikes on display plus a good selection of traded-in second hand machines in their showrooms, on a Saturday afternoon, around the time Blow-Up was being made, thousands of bikers from all over the country would congregate outside the bright-red Pride and Clarke shopfronts.

The contemporary press releases for Blow-Up made sure that attention was made to ‘the swinging world of fashion, dolly girls, pop groups, beat clubs, models and parties’ and one of the best lines in the film is when David Hemmings says to Veruschka at a party: ‘I thought you were meant to be in Paris!’ to which she stonily replies, ‘I am in Paris.’ The 26-year-old Veruschka, or Countess Vera Gottliebe Anna Gräfin von Lehndorff-Steinort, to give her full name, was an extremely tall German model, born just before the start of the war in East Pussia. Her father was said to have fainted when the extraordinarily long baby was born, but Veruschka hardly got to know him, as he was executed five years later for his part in the July Assassination Plot against Hitler in 1944. Around the time the film was released she told the press that she now wanted to be a proper actress: ‘I should like now to go into the movies,’ she said ‘but it is difficult – the men are so small.’ The experience of working with Hemmings must have scarred; he was eight or nine inches shorter than her six feet four.

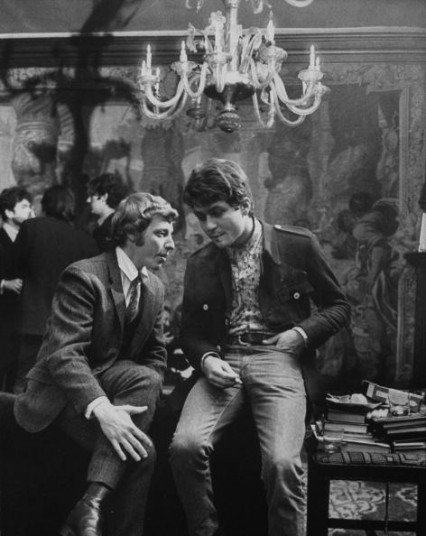

The party scene was shot in a house next to the Thames on Cheyne Walk. Owned by the designer Christopher Gibbs, it was full of Moroccan cushions and medieval tapestries. Antonioni paid beautiful people to be extras at £30 each (easily over an average week’s wage in 1966), [6] essentially just to get trashed. Paul McCartney once said, ‘I remember the word around town was “There’s this guy who’s paying money for people to come and get stoned at some place in Chelsea. And of course in our crowd that spread like wildfire…Everyone was being paid, like blood donors, to smoke pot.”’

Kieran Fogarty, in Jonathan Green’s Days In The Life, remembered the filming of the party scene in Blow-Up: ‘I was flung into this bedroom in Cheyne walk…plonked on the front of this bed with about another nine people on it and Antonioni tossed a couple of kilo bags of grass on the bed and said, “Right, get on with it.” It took five days. It just went on and on…people would stumble out going “Yeeeaahhh” and go gibbering back. Most of swinging London was there, every deb that was halfway decent looking, and wild they were too. Outrageously dressed, superheavy make-up …’

1966: Two men enjoying a conversation with each other while attending a party at Chrisopher Gibbs’ place. Photo by Terrence Spencer

One of the reasons the party scene took so long to film was that Veruschka, most of the time, really was in Paris. She would phone the house every few hours saying ‘Tell Michelangelo that my taxi crash …’. Whoever picked up the phone would wander around the house saying ‘It’s Veruschka! Her taxi’s crashed, she’ll be here in five or six hours’. Despite the camera running for almost a week, the scene at the party ended up just 30 seconds long.

Michelangelo Antonioni, who in 1960 won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes with his film L’Avventura, wrote an article in that year’s December edition of Films and Filming entitled: Eroticism – The Disease of Our Age. He asked ‘Why are literature and the entertainment arts so thick with eroticism today? It is the more obvious symptom of an emotional sickness.’ Six years later, after deciding to take no notice of himself whatsoever, Blow-Up became known as the first British mainstream film to show pubic hair, not to mention naked teenage models (including the 19 year old wife of John Barry, Jane Birkin). Not that anyone noticed particularly, as all around the country the public were treated to a ‘censored’ version of the film, not because the British Board of Film Censors or the local authorities were trying to protect the public’s morals, but because the brief moments of nudity, in those more sheltered days, were being trimmed out by projectionists to add to their private collections.

The film was released in March 1967, just as most people, especially in the capital, were getting rather bored with the idea of ’swinging London’. The result of which was mostly bad reviews from the critics in Britain – Peter Evans in the Daily Express, after describing Hemmings, aptly, as ‘a depraved choirboy,’ wrote: ‘What many people believed was to be some kind of tribute to the vibrant pace-setters turns out to be no less than an epitaph.’ He finished by describing the film as: ‘an unpleasant orgy of self-glorification.’

In Europe and America it was often a different story. Richard Schickel in Life magazine wrote: ‘This movie seems to me one of the finest, most intelligent, least hysterical expositions of the modern existential agony we have yet had on film’. Most of the contemporary reviews talked about the nudity, but none about how Hemmings’ photographer treated the women he encountered. Much of it uncomfortable to watch these days. But it is an enjoyable museum piece that, at least, gives us a good glimpse of groovy sixties London from the eye of an outsider. Additionally, if you want to stop the film at the right moments, you can see, briefly, Michael Palin and a young Janet Street Porter dancing in stripy Carnaby Street trousers during the the Yardbirds nightclub scene.

Four months after Blow-Up was premiered at the London Pavilion, The Sexual Offences Act was made law in July 1967. It decriminalised homosexual acts in private between two men, both of whom had to have attained the age of 21. Although the comments of Roy Jenkins, the Home Secretary at the time, captured the government’s attitude: ‘those who suffer from this disability carry a great weight of shame all their lives.’ Lord Arran, one of the original proposers of the bill, tried to minimise criticisms by making the qualification to what he called an ‘historic’ milestone: ‘I ask those [homosexuals] to show their thanks by comporting themselves quietly and with dignity … any form of ostentatious behaviour now or in the future or any form of public flaunting would be utterly distasteful …’

A few years later the motorcycle business started to change and during the seventies Japanese motorcycle companies such as Suzuki, Honda and Kawasaki took over from the old British and European marques. Alfred Clarke was an astute businessman (the nickname ‘shark’ wasn’t gained for nothing) and the Pride and Clarke firm was sold to Inchcape for about £3 million pounds in 1979.

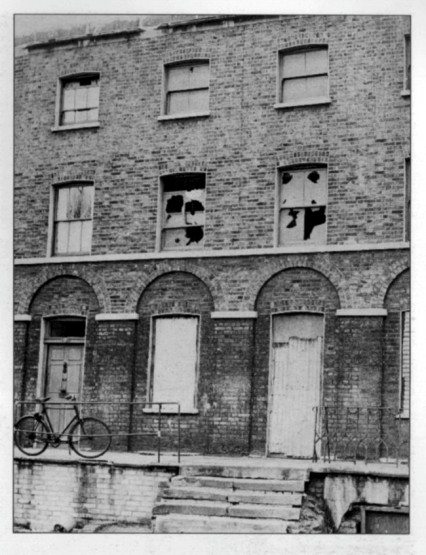

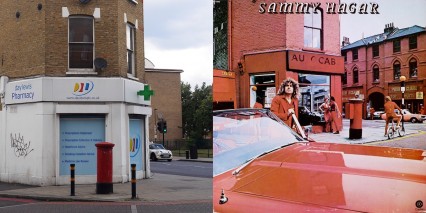

Then and Now: The Stockwell Road in 2015 and 1977 the year that Sammy Hagar’s ‘Red Album’ was released.

Before the company and the red paint were whitewashed from history, however, the striking red buildings of the Pride and Clarke showrooms had one more brush with fame. In 1977, the former Montrose vocalist Sammy Hagar was in London to record his second solo album at Abbey Road. Known to his fans, but to no one else, as the ‘Red Rocker’, someone at Capitol Records had the bright idea that the Pride and Clarke shops on the Stockwell Road were perfect for the cover of the so called Red Album. So as not to look too downmarket, he was told to stand next to an expensive American car, also coloured red. There is no record of what Sammy Hagar made of the Stockwell Road and there’s no record left of the ubiquitous Pride and Clarke shops. Unless you look very, very closely.