Charlie Chaplin was woken up on the morning 17 September 1921 while in his bed at the Ritz Hotel on Piccadilly. “Visitors from Hoxton” he was told, and from outside the window he could hear children singing a song over and over again:

When the moon shines bright on Charlie Chaplin

His boots are cracking, for want of blacking

And his little baggy trousers need mending

Before we send him to the Dardanelles

The song had originally been written in protest about Chaplin not enlisting during WW1 (it was said that he had tried, but at 5 feet 4 inches tall and not much more than 126 pounds was told he was too small) but by 1921 the song had lost its original connotation or at least it had to the group of children from Hoxton School that had walked across London to see him.

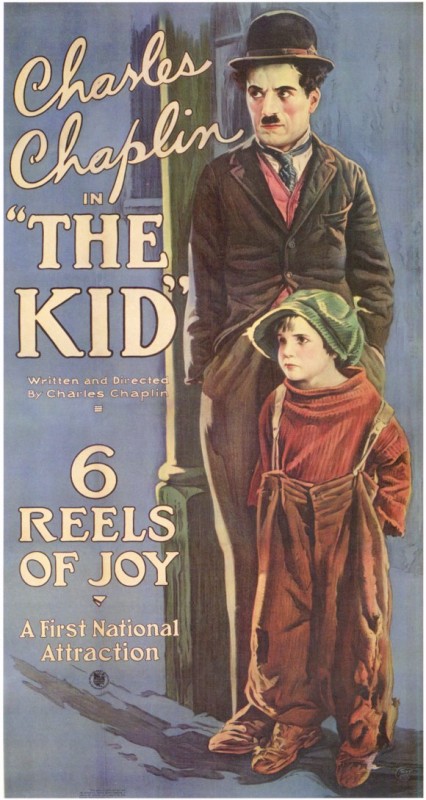

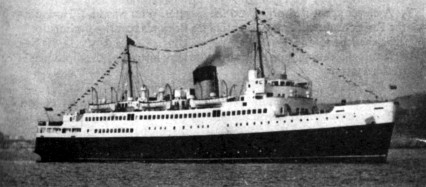

Chaplin had arrived in England from America only a week earlier, disembarking at Southampton after a pleasant and sunny voyage. He had sailed across the Atlantic on the RMS Olympic, the elder sister ship of the Titanic but now, of course, complete with the requisite number of lifeboats and luxuriously re-fitted after life as a troopship during WW1. The comedian had come back to England mainly to promote his new and first full-length (six-reeler) film called ‘The Kid’. Already a huge success in America it eventually became the second highest grossing film of 1921.

The Manchester Guardian, in rather a gushing style – although not that dissimilar to most other newspapers describing the event – wrote of the first glimpse of the homecoming Hollywood star:

Mr Chaplin just bubbled over with good nature and good humour. He poured out smiles and laughter and merry jokes in bumper measure, and all with the utmost simplicity and perfect freedom from affectation.

The Mayor of Southampton greeted Chaplin and began speaking rather nervously, with an apology about the weather, “It does not always rain in England…” Chaplin quickly interrupted, “I am an Englishman, Mr Mayor,” he said, “and English weather, whatever it is, is good to see. It was raining, I remember, when I went away nine years ago.

Chaplin was now an incredibly rich man but his childhood in Walworth had been a desperately poor one. Both his parents, Charles and Hannah Chaplin, were music hall performers but of no great fame. When Charlie was just three, Charles Snr left the family home after his wife gave birth to a boy whose father was Leo Dryden – another music hall performer. Not long after the birth Dryden came and forcibly took his child, Charlie’s half-brother, away from Hannah.

Struggling financially, Hannah Chaplin had a breakdown in 1895 and the following year, along with Charlie and his brother Sydney, entered the Lambeth Workhouse. Although within a few weeks, however, the two boys were sent to Hanwell School for Orphans and Destitute Children.

In 1903, after further breakdowns, Hannah was placed in the Cane Hill Lunatic Asylum in Surrey. Chaplin later wrote about a visit to see her in 1912, just before he left to live in America:

It was a depressing day, for she was not well. She had just got over an obstreperous phase of singing hymns, and had been confined to a padded room. The nurse had warned us of this beforehand. Sydney saw her, but I had not the courage, so I waited. He came back upset, and said that she had been given shock treatment of icy cold showers and that her face was quite blue. That made us decide to put her into a private institution – we could afford it now.

The brothers took their mother from Cane Hill and placed her at Peckham House – a private asylum in south London that cost 30 shillings a week. Not an inconsiderable sum in 1912.

Chaplin had been performing to audiences from the age of five – it was said that he was literally pushed on to a stage when an audience started jeering after his mother when she suddenly lost her voice half way through a song. By the age of 19 he had become a member of Fred Karno’s prestigious music hall troupe, and it was with them that he first took him to America in 1910 (one of the other members of Karno’s company was Stanley Jefferson who would later become known as Stan Laurel). On a second visit in 1912 Chaplin caught the eye of Mack Sennett and he began to work in the still very young film business. Within a few years he had appeared in more than sixty films, most of which he had directed himself. By 1918 Charlie Chaplin was one of the most famous men on the planet.

When Chaplin stepped off the train onto platform 14 at Waterloo Station, just a mile or so away from where he had grown up as a child, he was visibly shocked at the thousands and thousands of people waiting ready to greet him. “A fierce roar of the great crowd smote his ears,” wrote one newspaper, while the Times wrote, “At Waterloo the stage might have been set for the homecoming of Julius Caesar, Napoleon, and Lord Haig rolled into one.”

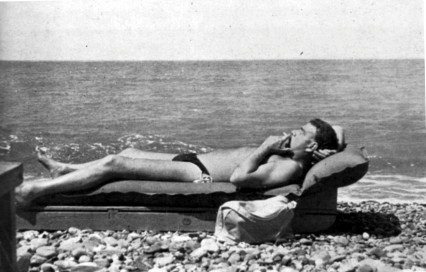

The police managed to get Chaplin into a waiting car which then drove down to the Ritz on Piccadilly. Another enormous crowd was waiting and ‘Everybody – including the police – went mad,’ reported the Manchester Guardian. Chaplin, his hair dishevelled, but bronzed by his voyage and dressed immaculately in a grey overcoat stood up in the car and shouted:

Thank you, very much, for this generous, kind and affectionate welcome. This is a great moment for me. I cannot say much. Words are absolutely inadequate.

The police were almost overpowered by the boisterous and excited crowd and there was a struggle on the steps of the hotel before they managed to get Chaplin inside. The crowd continued cheering until he appeared at a first-floor window where be broke up a huge bunch of carnations and threw them down to the crowd. A few days later he received a letter (one of thousands, many of them begging), “My boy,” it read, “tried to get one of your carnations and his hat was smashed. I enclose you a bill of 7s. 6d. for a new one.”

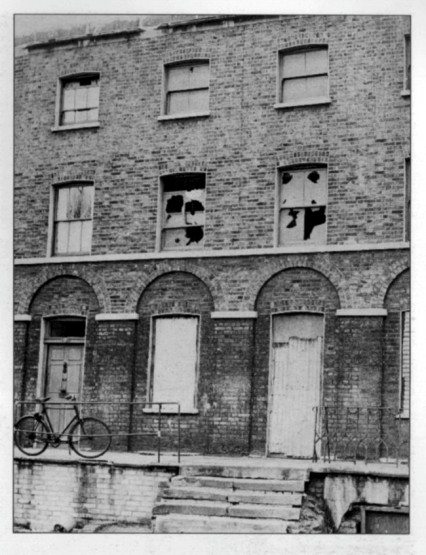

Chaplin told the press that he was tired and needed to rest but actually soon slipped out of the Arlington entrance of he hotel and took a taxi to Waterloo Bridge and then, on his own, he walked to Lambeth Walk an old haunt of his childhood. A few days later, on another trip to south London, he visited 3 Pownall Terrace in Kennington (the street would be demolished in 1968) where he had lived in a little room at the top of the house.

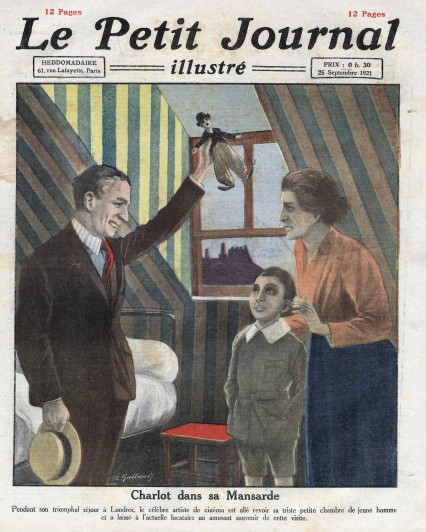

It was now occupied by a Mrs Reynolds, ”many’s the time I’ve banged my head on that sloping ceiling,” he said to her after she had taken him to see his old room. Mr Charles Robinson, described as Chaplin’s manager by the Daily Mirror, told the newspaper in an interview in 1921, that the attic scenes in The Kid were based on a replica of that room in Charlie’s old ‘diggings’ in Kennington.

Le Petit Journal dated 25th September 1921. Chaplin is seen visiting the Lambeth room, where he once lived and which had inspired his film ‘The Kid’.

The house in Pownall Terrace in Lambeth, where Charlie Chaplin once lived. It was demolished in 1968.

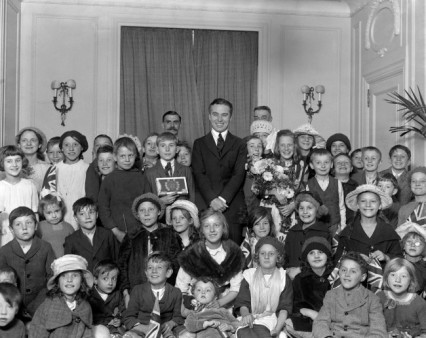

Back at the Ritz, on the morning of the 17th of September, Chaplin got dressed and walked into the sitting room of his suite to meet the young visitors from Hoxton. He found fifty excited boys and girls from the Hoxton school. One boy, called Charles Loughton, stepped forward and handed him a box of cigars and a letter. It read:

You were one of us. You are now famous over the world. But we like to think you were once a poor boy in London as we are. You are now a gentleman, and all gentlemen smoke cigars. So we have chosen a box as a little gift to ‘Our Charlie.’

A young girl, Lettie Westbrook aged thirteen, gave Charlie a bouquet with a note saying, “with our thanks for all the fun you give to us.”

After Chaplin had given each child a package of “candy,” he impersonated an old man in a picture gallery. By a skilful use of his overcoat, hat, and stick, he appeared to grow gradually to a height of some nine feet in order to look at the highest pictures, and the children screamed with laughter.

Three weeks after Chaplin met the boys and girls from Hoxton School he left London, via Waterloo again, for New York, this time on the Cunard liner Berengaria. He had also decided, along with his brother Sydney, to bring his mother back with him to California. After a particularly harsh and tragic life much of which had been spent in workhouses and mental institutions Hannah Chaplin was being properly looked after in a home in Los Angeles.

During the production of ‘The Kid’ Chaplin had met a 12 year old girl called Lita Grey who appeared as the flirtatious angel in the dream sequence at the end of the film. Three years later he cast her again, this time as the female lead, in ‘The Gold Rush’. During the early stages of the production the 35 year old Chaplin became ‘romantically’ involved despite Lita being only 15. It wasn’t long before Lita discovered she was pregnant and was quickly replaced in the film by another of Chaplin’s lovers Georgia Hale.

Grey and Chaplin were wed on November 25th 1924 in Empalme, Mexico. The New York Times, reporting on the event, listed her age as 17. They had two children, Charles Jnr born in 1925 and Sydney born the following year. On August 27th they were divorced due to ‘extreme cruelty’. Chaplin was ordered to pay $600,000 and $100,000 in trust for each child – the world’s largest divorce settlement at the time.

Exactly a year after the divorce Chaplin’s mother, the woman whose life he had based so many of his female characters, and who had probably been suffering from the symptoms of Syphilis for over twenty years, died at the Physicians’ and Surgeons’ Hospital in Glendale in August 1928.