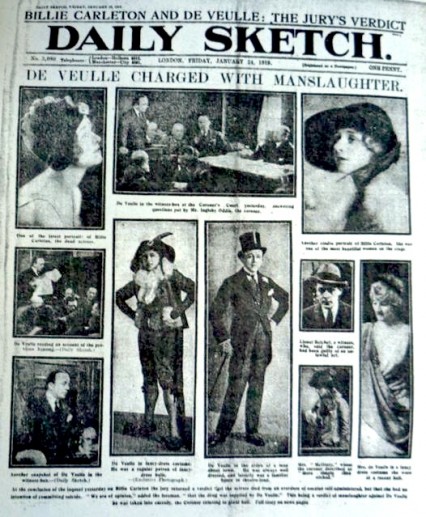

Seventeen days after World War One had ended, a young pretty actress called Billie Carleton had a starring role at the huge Victory Ball held at the Albert Hall on 28th November 1918. One newspaper described her appearance:

It seemed that every man there wished to dance with her. Her costume was extraordinary and daring to the utmost, but so attractive and refined was her face that it never occurred to any one to be shocked. The costume consisted almost entirely of transparent black georgette.

Just a few months previously Tatler magazine had described one of her appearances on a London stage, saying that she had:

Cleverness, temperament and charm. Not enough of the first, and perhaps too much of the latter.

Carleton was well on the way to becoming a big star by now but her career was continually being held back by what was becoming a rather obvious and large drug habit. And, unfortunately, the girl with too much charm and the daring costume was found dead in her Savoy Hotel suite by her maid the morning after the Victory ball. She was just 22 years old.

A gold box containing cocaine was found at her bedside and at the inquest it was suggested that she had died of ‘cocaine poisoning’. Although it was more likely that a combination of cocaine and some kind of depressant helped end her short life.

The subsequent court case revealed a highly dubious way of life for a young woman of the time. Witnesses described her heavy cocaine and opium use and it became known that the London-born actress, who incidentally never knew her father, was involved with three ‘sugar daddies’. Two of these helped her financially – she had a very expensive life-style to maintain including a permanent suite at the Savoy Hotel – while the other, a married dress-designer called Reggie de Veulle, was more of a drug-taking partner.

It was de Veulle who had given Carleton the cocaine that apparently had killed her. He had bought the drug a few days previously from a Scottish woman called Ada and her Chinese husband Lau Ping You who both lived on the Limehouse Causeway. In court it came to light that de Veulle had been involved in a previous homosexual blackmail case and with a headline that read “An Opium Circle. Chinaman’s Wife Sent to Prison. High Priestess of Unholy Rites” the normally staid Times reported that both de Veulle and Carleton had been at an all-night ‘orgy’ in a Mayfair flat where the women wore flimsy nighties and the men silk pyjamas while smoking opium.

The press and the court, however, considered Billie Carleton a tragic innocent victim describing her as having:

“a certain frail beauty of that perishable, moth-like substance that does not last long in the wear and tear of this rough-and-ready world.”

Ada was sentenced to five months hard labour, her husband escaped with just a ten pound fine while, despite the judge’s direction, the jury acquitted Carleton’s friend Reggie de Veulle of her manslaughter. He admitted, however, to supplying Carleton cocaine and was imprisoned for eight months.

The death of beautiful girl from drugs combined with the involvement of a Chinese man created what was to become the first big drug scandal of the 20th century. The press, as they say, whipped themselves into a frenzy and the newspaper Pictorial News, for instance, ran a series of pieces about the East End of London and what they described as the encroaching ‘Yellow Peril’.

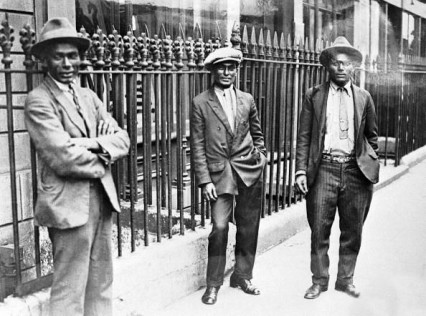

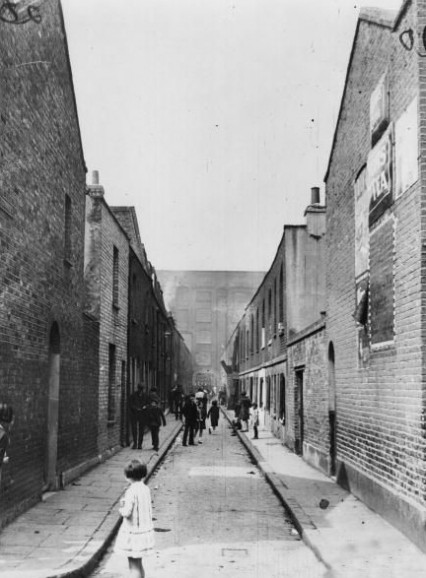

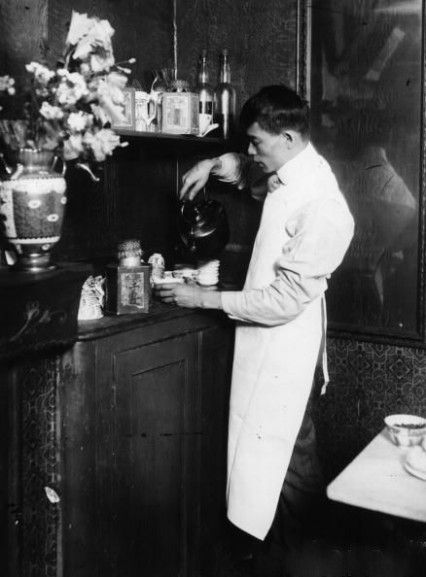

In the real world the so-called ‘yellow peril’ was actually a small, relatively law-abiding Chinese community which had been based around the Limehouse docks area from around the beginning of the 19th century. By the beginning of the twentieth century there were two separate communities in the area – the Chinese from Shanghai were based around Pennyfields and Ming Street (between the present Westferry and Poplar DLR stations) whereas the immigrants from Southern China and Canton lived around Gill Street and the Limehouse Causeway. By 1911 the whole area had started to be called Chinatown by the rest of London.

Considering that there were rarely more than a few hundred Chinese people living around Limehouse before and after the first world war (in fact Liverpool had a far larger Chinese population), the East End Chinatown had an extraordinarily bad reputation.

It wasn’t just the fault of a slavering press looking for scandal and writing lurid headlines about opium dens and the white-slave traders there were also numerous writers, novelists and even film-makers that were helping to greatly exaggerate the danger and immorality of the area. At times it seemed that Limehouse was almost singlehandedly responsible for corroding the moral backbone of the British middle-classes.

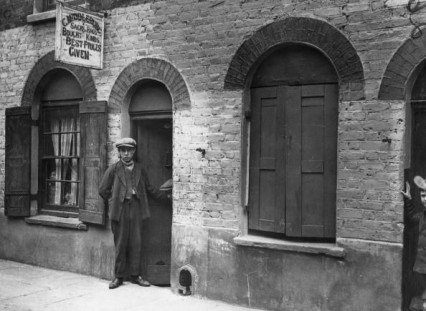

HV Morton the famous travel essayist and journalist wrote about Limehouse in his book ‘The Nights of London’ in 1926:

The squalor of Limehouse is that strange squalor of the East which seems to conceal vicious splendour. There is an air of something unrevealed in those narrow streets of shuttered houses, each one of which appears to be hugging its own dreadful little secret… you might open a filthy door and find yourself in a palace sweet with joss-sticks, where queer things happen in a mist of smoke……The silence grips you, almost persuading you that behind it is something which you are always on the verge of discovering; some mystery of vice or of beauty, or of terror and cruelty.

The fact that the Chinese community liked to gamble and smoke opium was bad enough but it seemed to be the fear of sexual contact between the races (which the drug-taking of course only exacerbated) that frightened so many people; especially the newspaper editors of the time. ‘White Girls Hypnotised by Yellow Men’ shouted the Evening News, writing that it was the duty ‘of every Englishman and Englishwoman to know the truth about the degradation of young white girls’.

Thomas Burke, writing for an apprehensive suburban readership that lapped up his writings, even in the US, wrote a number of ‘sordid and morbid’ short stories and newspaper articles about the Limehouse Chinatown. One of his stories, from a collection entitled Limehouse Nights, was called ‘The Chink and the Child’ and was actually made into a successful film called ‘Broken Blossoms by DW Griffiths starring Lilian Gish.

Broken Blossoms directed by DW Griffiths in 1919, its alternative title was The Yellow man and the Girl. Lillian Gish was 26 at the time.

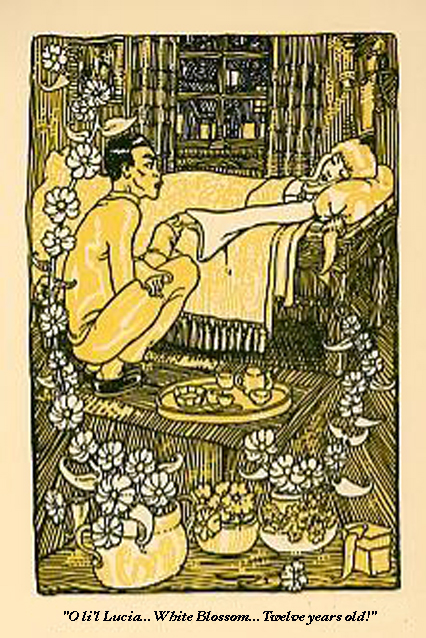

Another of the stories from Limehouse Nights was called Tai Fu and Pansy Greers and was about a young white woman who submitted her self to a ‘loathly, fat and old’ Chinese man:

He was a dreadful doper. He was a connoisseur, and used his selected yen-shi (opium) and yen-hok (a needle used to cook the opium pellet) as an Englishman uses a Cabanas…She went to him that night at his house in the Causeway. He opened the door himself, and flung a low-lidded, wine-whipped glance about her that seemed to undress her where she stood, noting her fault and charm as one notes an animal. He did not love her; there was no sentiment in this business. Brute cunning and greed were in his brow, and lust was in his lips… What he did to her in the blackness of that curtained room of his had best not be imagined. But she came away with bruised limbs and body, with torn hair, and a face paled to death.

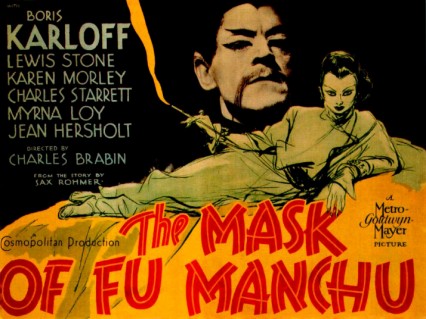

Sax Rohmer was another former journalist that used his knowledge of Limehouse to write popular fiction, notably the incredibly successful Fu Manchu novels about a depraved Chinese man whose evil empire’s headquarters was based improbably in Limehouse:

Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present…Imagine that awful being and you have a mental picture of Dr Fu Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories went on to inspire over thirty films and television series throughout the following decades. However Rohmer also wrote a novel called Dope in which a character called Rita Dresden was unashamedly based on Billie Carleton. A silly socialite in the same novel called Mollie Gretna envies the Scottish wife of the Chinese drug dealer:

I have read that Chinamen tie their wives to beams in the roof and lash them with leather thongs. I could die for a man who lashed me with leather thongs. Englishmen are so ridiculously gentle to women!

Four years after the death of Billie Carleton, a girl of roughly the same age called Freda Kempton, was found dead after an overdose of cocaine. At the inquest of the young nightclub ‘dance instructress’ the press found out that on the night of her death she had been with a notorious drug dealer called, rather brilliantly, Billy ‘Brilliant’ Chang at his Regent Street restaurant. He told the Coroner at her inquest “Freda was a friend of mine but I know nothing about the cocaine. It is all a mystery to me”. Chang during the inquest was portrayed as a man with a magnetic attraction to white women and one newspaper wrote that after the verdict:

“Some of the girls rushed to Chang, patted his back, and one, more daring than the rest, fondled the Chinaman’s black, smooth hair and passed her fingers slowly through it.”

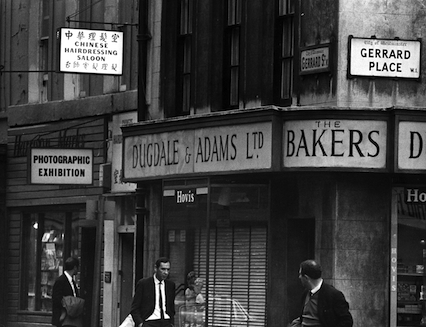

According to the coroner there was no proof that he was linked to the death but the police, and the press, were convinced that he was. By now Chang had sold his restaurant in Regent Street and opened the Palm Court Club in Gerrard Street. There’s a strong possibility that Chang was the first Chinese man to open a business in the street which was to become the centre of the new Chinatown in London forty or so years later.

Due to continuous police raids Chang sold up again and moved to Limehouse where he opened the Shanghai Restaurant. His flat was at 13 Limehouse Causeway (coincidentally just four doors away from where Mr and Mrs Lau Ping You lived) below a top floor let to two Chinese sailors and it was here in 1924 when his luck finally ran out.

The police had already twice raided his Limehouse flat and although they found no drugs on one occasion they found two chorus girls in his bed. On the third attempt however, and armed with evidence from a drug addicted actress called Violet Payne, they found a wrap of cocaine behind a loose wooden board and they arrested the man who may have been controlling 40 per cent of the London cocaine trade.

During the trial, the press, again pruriently slavering, had a field day. The World Pictorial News wrote:

“Sometimes one girl alone went with Chang to learn the mysteries of that intoxicatingly beautiful den of iniquity above the restaurant. At other times half-a-dozen drug-frenzied women together joined him in wild orgies.”

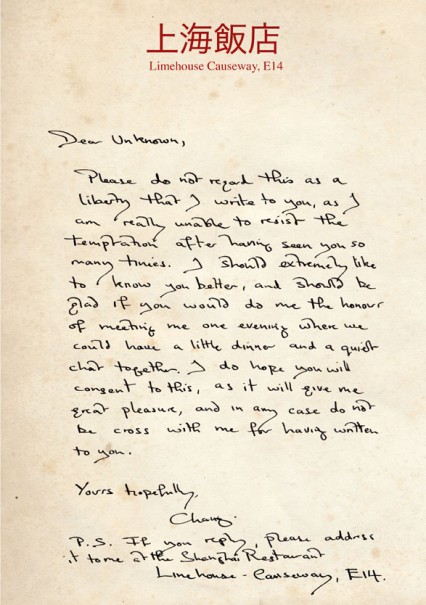

As well as the cocaine the police found at Chang’s home a pile of identical handwritten letters:

Dear Unknown – Please do not regard this as a liberty that I write to you, as i am really unable to resist the temptation after having seen you so many times. I should extremely like to know you better, and should be glad if you would do me the honour of meeting me one evening where we could have a little dinner and a quiet chat together. I do hope you will consent to this, as it will give me great pleasure, and in any case do not be cross with me for having written to you.

Yours hopefully, Chang.

P.S. – If you reply, please address it to me at the Shanghai Restaurant, Limehouse-Causeway, E14.

Chang was sentenced to fourteen months in prison after which he was deported. His ship left from the Royal Albert Docks and it was reported that one girl shouted out as he was leaving ‘Come back soon, Chang!’.

The local council, maybe because of the’Yellow Peril’ nonsense exaggerated by the wild press reports, lurid novels and films, started to clear the slums in the Limehouse area. This started to break up the original London Chinatown and a few years later the Second World War practically finished the job as the area was razed to the ground by the wartime bombing.

The Chinatown we know today began not long after the war when a few restaurants opened in Lisle Street, the road that runs parallel to Gerrard Street where Brilliant Chang briefly ran his nightclub. The area was on the edge of Soho where foreign restaurants had long been the norm and the rents were cheap for a West End central location.

The number of restaurants increased mainly because of returning servicemen who had discovered a taste for food from the far East. However, when in 1951 the UK government finally recognised Mao Zedong’s communist regime, the diplomats and staff of the now defunct Chinese Nationalist Embassy suddenly had to find new jobs. A lot of them, including the famous restauranteur and cookery writer Ken Lo choose to open Cantonese restaurants in the area we now know as Chinatown.

A lot of the information and inspiration for this post comes from the really excellent book Dope Girls by Marek Kohn.