“Will you marry me? It’s risky, but you’ll get fucked regularly”.

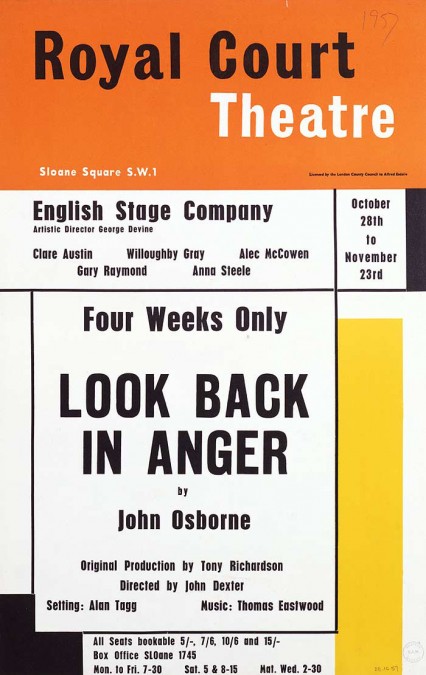

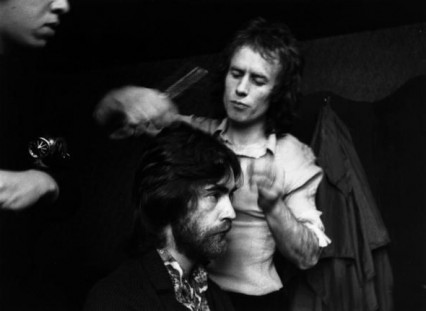

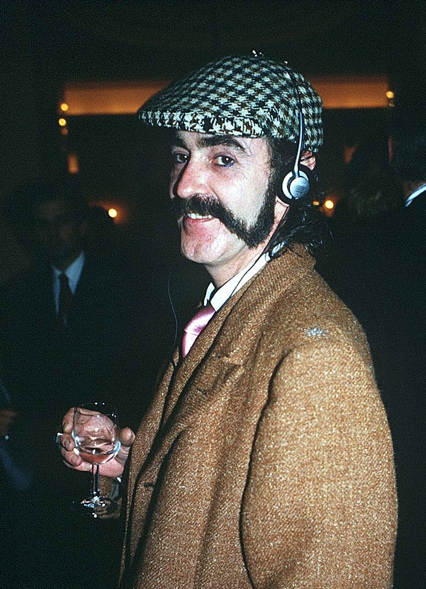

Four months before the Suez crisis, the moment in history when a begrudging, drizzly and grey Britain belatedly realised it wasn’t a super-power any more, the newly re-opened Royal Court Theatre, situated on the east side of Sloane Square in Chelsea, premiered the first play by a 26 year old actor called John Osborne.

Look Back In Anger was written in seventeen days while sitting in a deckchair on Morecambe pier . The legend is, of course, that Osborne’s play was an immediate success and in a flash British theatre was changed forever. Replaced by plays set in drab working working class northern bed-sits, the posh drawing-room dramas from playrights like Terrence Rattigan and Noel Coward, were seemingly banished overnight.

“I think the writer is trying to say: ‘Look how unlike Terence Rattigan I am, Ma!”.

The next day the director of the play Tony Richardson and Osborne sat in the little coffee shop next to the Royal Court theatre utterly depressed. Richardson broke the silence, and said:

“But what on earth did you expect? You didn’t expect them to like it, did you?”

Although the play was generally initially dismissed by most of the critics, a prescient 39 year old Kenneth Tynan wrote in the Observer -

“All the qualities are there, qualities one had despaired of ever seeing on the stage … I doubt if I could love anyone who did not wish to see Look Back in Anger.”

‘Anger’, as luvvies are apt to call the play, initially took very little money and the production was seen pretty much as a miserable failure. However, a few weeks into the run, the BBC decided to broadcast a short excerpt of the play one evening. The listeners liked what they heard, decided to go and see the play for themselves and takings immediately doubled at the box office. The effect snowballed and the play eventually transferred to the West End, subsequently to Broadway and was made into a film in 1958 starring Richard Burton. It certainly wasn’t overnight but Osborne had now become a very famous angry young man indeed.

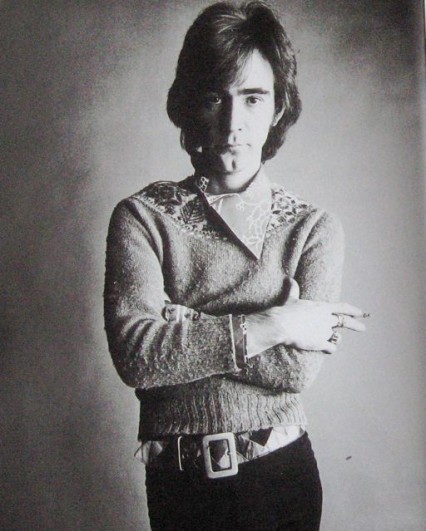

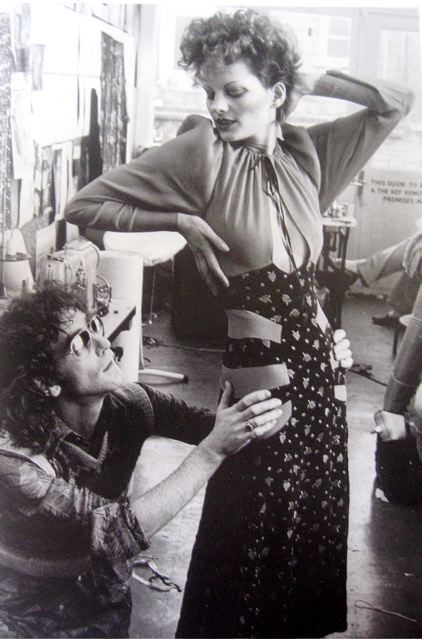

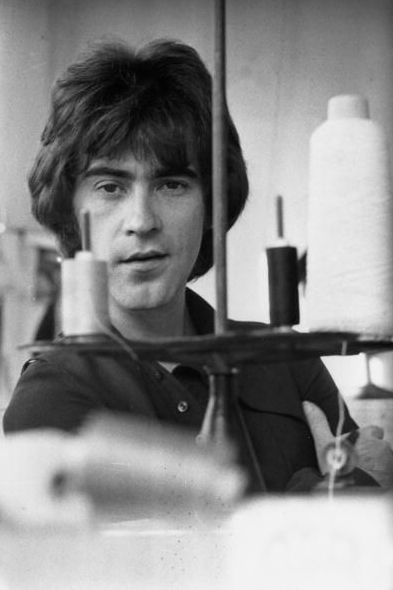

Osborne went on to write successful plays such as The Entertainer (starring Sir Laurence Olivier), Luther and A Patriot For Me. He also won an oscar for his adaptation of Tom Jones in 1963. He occasionally continued acting and his acting role in the 1971 film Get Carter was highly regarded and indeed was a brilliant menacing performance.

By the early seventies, however, depression and alcoholism set in. Bad reviews of his latest unfashionable plays didn’t help and were woundingly taken to heart. For instance the Financial Times’ BA Young’s review of his play Sense of Attachment which was put on in 1972 – “This must surely be an end to his career in the theatre”.

Writers, and artists in general, are often excused character defects and bad behaviour, for the sake of their art, but the treatment Osborne dealt out to most of the women in his life (and surprisingly, considering his behaviour, there were a lot of them with five wives and numerous affairs) was often extremely vile and misogynistic.

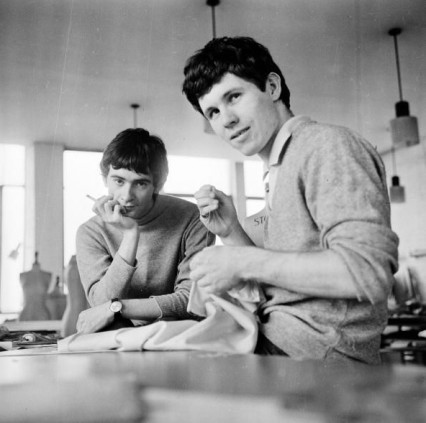

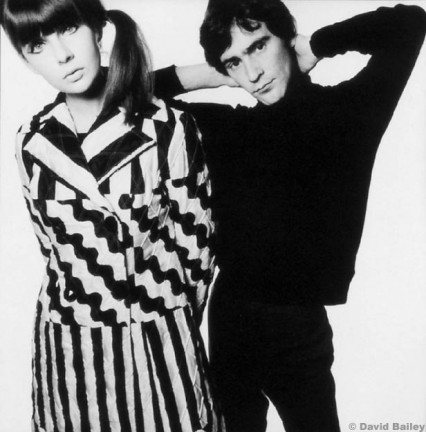

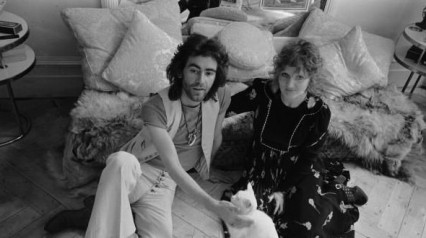

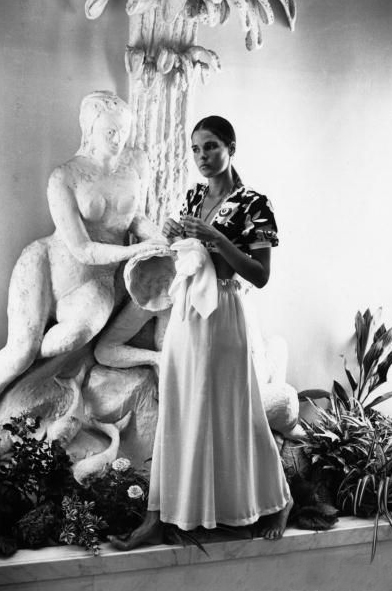

He left his first wife shortly before the opening of Look Back In Anger, and subsequently married Mary Ure the leading actress in the play and the film. They lived in a house in Woodfall Street just off the Kings Road a few hundred yards from The Royal Court Theatre. It was a marriage that would only last five years and his love life was, by the early sixties, extremely complicated. He was on holiday in the South of France with his mistress the beautiful flame-haired dress designer Jocelyn Rickard in 1961, while at home Mary Ure was giving birth to a son (to be fair it probably wasn’t Osborne’s). At the same time, in Italy, the journalist Penelope Gilliatt, and future mother of his daughter, received a charming marriage proposal by letter;

“will you marry me? It’s risky, but you’ll get fucked regularly”.

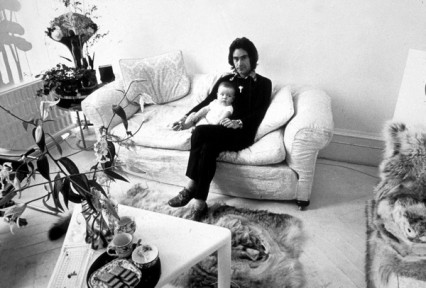

The letter worked (one day I will understand women) and a year later he married Gilliatt with whom he had a daughter. As usual the marriage was a relatively short-lived affair, and he married the actress Jill Bennett in 1968. Again the marriage soon became unhappy and the couple, both drinking extremely heavily, ended up viciously trying to put each other down. At a party she once shouted;

“Look at him, the poofter can’t even get it up.”

Jill Bennett committed suicide in 1990, two years after their divorce. Osborne decided to add a spiteful extra chapter to his memoirs – expressing pity that he hadn’t been able to look into her open coffin and “drop a good, large mess in her eye”. Peggy Lee’s ‘Is That All There Is?’ was played at her funeral.

When Gilliatt also fell in to irreversible alcoholism, their daughter Nolan, who had been brought up in New York with her mother, came to live with Osborne and his fifth wife Helen, then both living in Kent. It was a chance for him to make amends for his own unhappy childhood (his father died of TB when Osborne was 10, for which, some reason, he always blamed his mother) but after just three years Osborne threw Nolan out of his house, removing her from school for good measure. She was just seventeen. Her only crime seems to have been typical teenage sullen behaviour and a lack of interest in her father’s hard-drinking thespian friends. He once shouted at her;

“There is not one of them who is not worth a dozen low lifes like you.”

She went to stay with the family of a schoolfriend and Osborne never saw her again. “Nolan’s birthday,” he wrote in his diary when she turned 22, “God rot her.”

Likewise when his mother died in 1993, he wrote an article for the Sunday Times which included a first line, ‘A year in which my mother died can’t be all bad.’

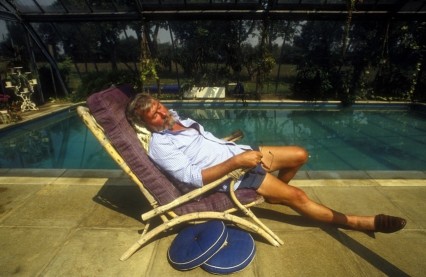

Osborne, who by this time had long left Chelsea’s Kings Road and started to act the country gent in Shropshire with his fifth wife Helen, died on Christmas Eve in 1994, 12 days after his 65th birthday. For once their marriage was a relatively devoted and private relationship. The last words that he wrote, found by his wife scrawled on a cigarette pack beside his deathbed in the hospital, were, “Sorry, I have sinned.”