No one really knows whether the Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison deliberately killed herself underneath the galloping hooves of Anmer – the Kings horse – at the 1913 Derby. Some say it was just a brave protest that went tragically wrong, after all a return train ticket was found in her handbag, along with an invitation to a suffragette event that evening.

Davison always knew that it would be a grand, even an ultimate, gesture that would get The Cause properly noticed by the public. She would have undoubtedly been pleased that out of all the thousands of suffragette protests in the early part of the twentieth century, it is her tragic protest that is still remembered today.

The Epsom Derby has always been enjoyed as a day out by Londoners of all classes but from when it was first run in 1780 it had traditionally been a royal event and indeed King George V and Queen Mary had both come to watch the race in 1913. The middle classes generally sat in the grandstands or even on top of omnibuses which made alternative makeshift stands in the middle part of the race-track. The centre of the track had always been a free part of the course to watch the Derby so it would have been here that the many working-class Londoners came to watch the race, smoking and drinking, and enjoying a rare day away from the grimy smoky city near by. Emily Davison would have walked through this crowd when she made her way to the famous sharp bend in the course known as Tattenham Corner.

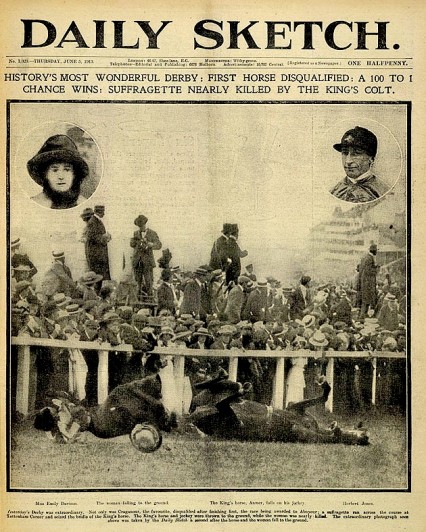

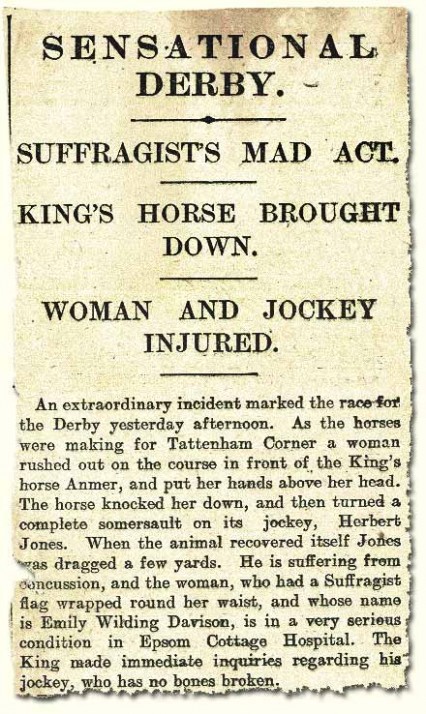

Davison waited for the race to start behind the barriers at the corner. When the first horses started to shoot by she slipped under the rail clutching on to her furled Suffragette tricolour banner of purple, white and green. Running out on to the track she futilely tried to hold on to the bridle of the King’s horse called Anmer which would have been galloping at around 35 mph. Screaming, the woman with the suffragette colours was immediately smashed down by the horse and jockey wearing the King’s colours. The next day the Daily Mirror wrote:

The horse struck the woman with its chest, knocking her down among the flying hoofs . . . and she was desperately injured . . . Blood rushed from her mouth and nose. Anmer turned a complete somersault and fell upon his jockey, who was seriously injured.

Four days after what the Daily Sketch described as; ‘History’s most wonderful Derby’, Emily Davison died of substantial internal injuries and a fractured skull. She never regained consciousness after the ‘accident’. By the side of the bed at Epsom Cottage Hospital was an unopened letter with ‘please give this to Emily’ written on the envelope. It was from her shocked and confused mother and Davison never read the words that said:

I cannot believe that you could have done such a dreadful act. Even for the Cause which I know you have given up your whole heart and soul to, and it has done so little in return for you. Now I can only hope and pray that God will mercifully restore you to life and health and that there may be a better and brighter future for you.

The jockey Herbert ‘Diamond’ Jones (so called because he had won the racing triple crown in 1900 when he rode the future King Edward VII’s ‘Diamond Jubilee’) was badly concussed and had his arm put in a sling. It was reported that he bravely shrugged off attempts to take him to the nearby hospital.

King George V wrote in his diary that “poor Herbert Jones and Anmer had been sent flying” on a “most disappointing day”. Queen Mary sent Jones a telegram wishing him well after his “sad accident caused through the abominable conduct of a brutal lunatic woman”.

If Davison had survived the collision with the King’s horse, it would have probably meant another visit to Holloway Gaol – the infamous North London women’s prison. She had already been there, amongst other prisons, six or seven times in the previous four years. The director of Public Prosecutions, even while Emily Davison was unconscious in hospital, stated that “if Miss Davison recovers it will be possible to charge her with doing an act calculated to cause grievous bodily harm”. It’s important to note that attempting suicide was illegal at the time, as it would be until 1961.

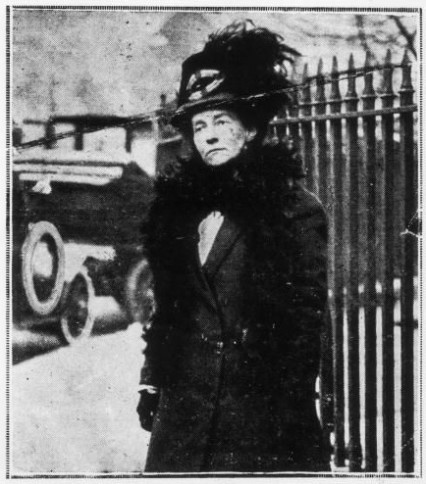

Emily Davison was born in Blackheath in South East London in 1872. Successful at school she won a place at Holloway College to study literature although she had to leave when her widowed mother couldn’t afford the £20 term fees. After a stint of teaching she earned enough money to return to university education and eventually ‘graduated’ from St Hugh’s College Oxford, women only allowed honorary degrees at the time.

Davison joined the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1906 – the organisation ran by Emmeline Pankhurst and her two daughters Christabel and Sylvia which had broken away from the older non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. That same year the journalist Charles E Hands writing in the Daily Mail patronisingly called the all-female members of the new WSPU – ‘Suffragettes’. However the newly coined word was reclaimed (much in the same way I suppose as derogatory words such as ‘queer’ or ‘nigger’ were reclaimed decades later) and taken up by the WSPU to separate themselves from the ‘more constitutional’ NUWSS who were still known as Suffragists.

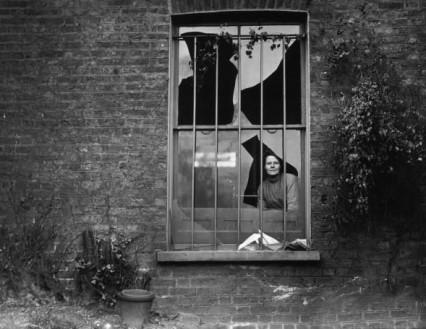

Emily Wilding Davison was perhaps the most militant member of the militant WSPU and from when she joined until she died she was continually in and out of prison. She threw metal balls labelled ‘bomb’ through windows, set fire to post boxes, hid in Parliament three times (notably on Census night in 1911) and continually went on hunger strike. The suffragettes who ‘hunger struck’ were initially released early so as to avoid martyrdom but soon the authorities started force feeding to, in the end, disastrous publicity.

In 1912, in protest to another bout of painful force-feeding, and which may be a clue to her actual plans on the fateful Derby day of 1913, she threw herself off a balcony at Holloway prison. She was saved from her suicide attempt by the netting three floors below. She later wrote;

“I did it deliberately, and with all my power, because I felt that by nothing but the sacrifice of human life would the nation be brought to realise the horrible torture our women face. If I had succeeded I am sure that forcible feeding could not in all conscience have been resorted to again”

It seems unlikely, therefore, that Davison only a year later was only attempting to get to the other side of the course when Anmer unavoidably thundered into her at the Epsom Derby.

The WSPU cleverly used Emily Wilding’s funeral as a spectacular publicity event knowing that it would be filmed by the relatively new, but extremely popular, news-reel cameras. On Saturday 14 June 1913, to the drumming of ten brass bands, 6,000 women marched through the streets of London with huge crowds watching from the sidelines, the younger suffragettes dressed in white while their elders dressed in a more traditional black. Bricks were reported to have been thrown at the coffin and the carriages behind the first of which contained Davison’s close family including her mother and Miss Morrison – ‘Miss Davison’s intimate companion’.

‘Diamond’ Jones never properly recovered after he and his horse crashed into Davison during the 1913 Derby. He lost three of his brothers in the First World War and his career started to go downhill and he retired in 1923 after a pulmonary haemorrhage.

It’s not that well known that in 1928 when the former leader of the WSPU, and perhaps the most famous of all the suffragettes, Emmeline Pankhurst died, Herbert Jones travelled to London for the funeral. The wreath that he left said

To do honour to the memory of Mrs Pankhurst and Miss Emily Davison.

On 17 July 1951, Jones was found dead in a gas-filled kitchen by his 17 year old son. The coroner subsequently recorded a verdict of ‘suicide while the balance of his mind was disturbed’. The former jockey had once said that he was ‘haunted by that woman’s face’ all his life. It wasn’t just one suicide that was connected to the fateful collision at the Epsom Derby on that humid June day in 1913.

Less than a week before Emily Davison’s tragic death at the Derby, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring was premiered in Paris at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The complex and modern music caused chaos in the audience which soon degenerated into a riot. At the interval the Parisian police had to intervene. It was the slight discordant notes behind the initial bassoon solo at the beginning of the piece that set off the violence.

Incidentally, due to more pressing matters such as musical notes being slightly out of tune, France didn’t get round to allowing women to vote until 1944. It was 27 years later in 1971 when women in Switzerland were only allowed into the voting booth. While male voters had it all to themselves in Portugal until 1976.